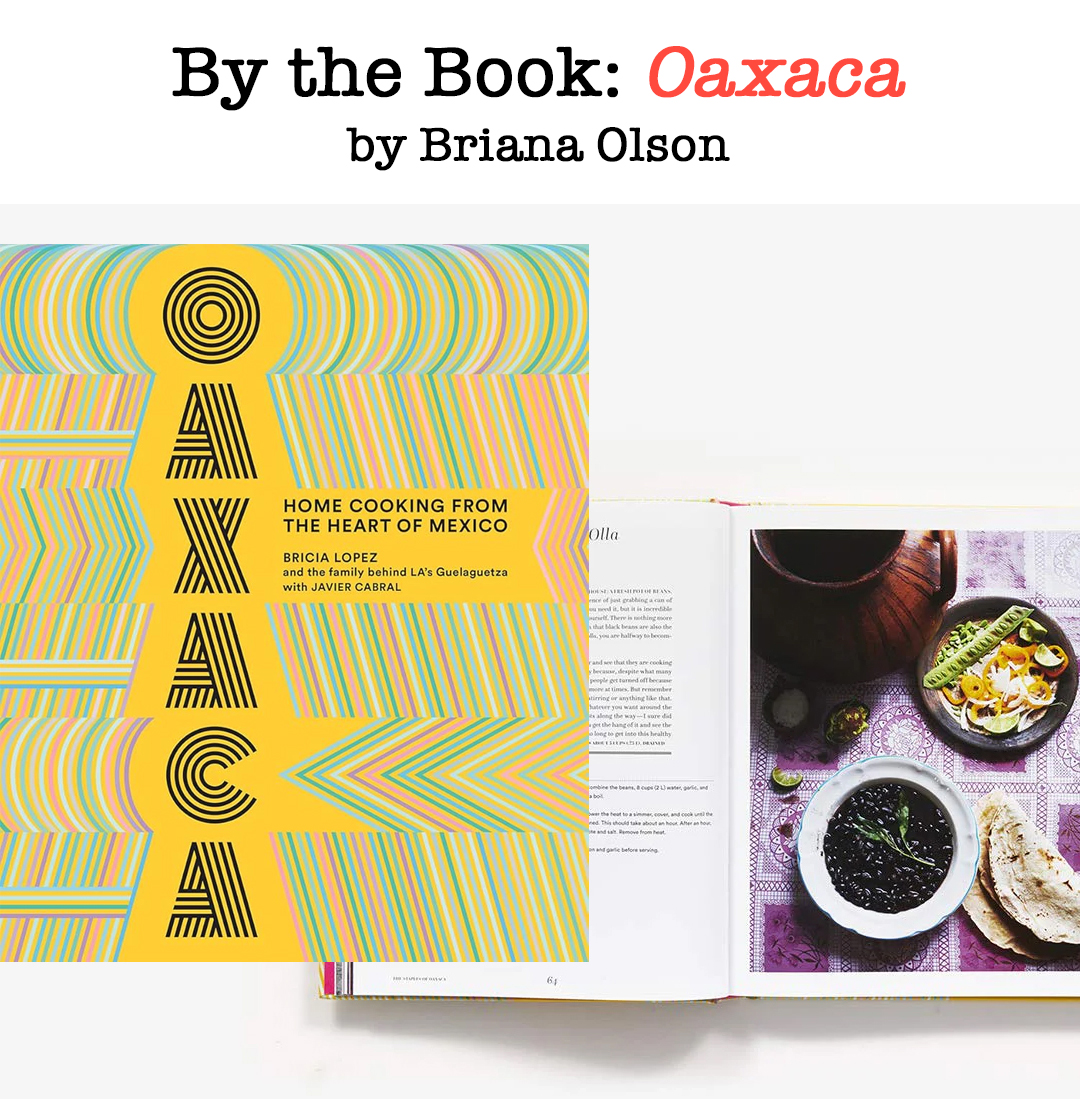

Oaxaca: Home Cooking from the Heart of Mexico

by Bricia Lopez and the family behind LA’s Guelaguetza with Javier Cabral

Call me old school, but I’m skeptical of cookbooks full of pretty pictures. Nothing against gorgeous photography; it’s just that there’s a certain class of cookbook that seems to be less about cooking and more about selecting a food-adjacent object to display artfully on the coffee table. Maybe because I suspect promotion to be the heart of the matter, or maybe because I’m a generalist in the kitchen, I also don’t tend to gravitate toward cookbooks that share their name (or most of their menu) with a restaurant. That’s two strikes (or two prejudices, anyway) against Oaxaca, which is bookended with sexy photo essays and whose introduction includes a lengthy overview of Guelaguetza, founded by the author’s family in LA in 1994. But prejudices are made to be crushed, right?

Oaxaca turns out to be a cookbook that, if you wish, can serve as both coffee table book and reference book (as long as you’re okay with a few salsa-smeared pages in your coffee table book, that is). It reminds me slightly of Marcella Hazan’s cookbooks, with serious recipes (think masa from scratch or estofado de pollo) and a serious approach to ingredients tempered with an understanding of what may or may not be as abundantly available in the United States as in southern Mexico. For those with limited time (or ingredients) at their disposal, there are some simpler recipes, like chilaquiles and entomatadas, alongside the infamously complex specialties of the region.

The title of the book’s first chapter, “The Staples of Oaxaca,” says a lot about the philosophy behind this cookbook. While there are plenty of detailed recipes—molotes de masa con papas y chorizo, for example—Oaxaca is all about building blocks. There’s a stand-alone recipe for bean paste (you’ll want it for your memelas), a chapter of moles and a chapter of salsas. Unlike mole recipes that culminate in the making of a single, elaborate dish, several of the mole recipes here are simply that: recipes for mole, to be used however you wish. I love this; like I said, I’m a generalist in the kitchen, and none too keen, besides, on being told exactly what to do. Too, I like that I can make a batch of mole rojo or coloradito to serve with braised chicken, then save the leftover sauce for enmoladas.

Ultimately, Oaxaca is a charming, accessible, and, for lack of a better word, honest collection of recipes. Not all the dishes are showy; in fact, merely labeling chapters “Breakfast” and “Family Meals” highlights the rustic roots of Oaxacan cooking. Sure, you can dedicate an entire afternoon to mole negro, but you can also make a single-pot dish like pollo en orégano. Slick as the book’s photos are, they convey much the same thing: the reason for Oaxaca’s rich culinary heritage is not only the people but the land, where chile and cactus, corn and agave, beans and cacao have grown for centuries.

Even the history of the family’s restaurant, when I finally read it, touched me unexpectedly. I won’t call this a beginner’s cookbook, but it is infused with can-do spirit. It’s also filled with the warmth and generosity underpinning the annual Guelaguetza—a celebration of exchange and collaboration whose name traces back to the Zapotec word for offering. And if you’ve been wanting to move past that green chile enchilada casserole, why not now? You might discover that it’s not that hard—or that it is, but it’s worth it.

Who’s Your Source?

Luckily, most of “the Oaxacan essentials,” as Lopez and crew call them, can be found with relative ease in New Mexico. For chiles, I often hit up the cash-only Chile Konnection in Albuquerque; their variety is wide, the quality good, and they also carry powdered chile and other staple spices and foods. El Mezquite Markets are another fairly reliable source, although sometimes their chiles are mislabeled (or not labeled at all), and the staff don’t always know what’s what. (Keep in mind that anchos—dried poblanos—are also known as pasillas, and will sometimes be labeled as such in local markets; don’t buy them thinking they’re pasillas oaxaqueñas.) El Mezquite and El Super are also good spots to look for Mexican-style crema and Mexican cheeses, as well as hibiscus flowers, dried avocado leaves, and some Mexican cuts of meat. El Super, as well as Tortilleria La Poblana and La Mexicana Tortilla Co., carries fresh masa if you don’t want to make your own. Note that “masa preparada” is masa with lard already mixed in, ready to go for tamales. That lard is likely the commercial stuff, which is typically hydrogenated; for the pure stuff, hit up Polk’s Folly Farmstand in Cedar Crest.

That said, good luck finding fresh epazote to make Oaxacan frijoles de olla. Dried, the herb loses much of its pungency, but it’s still worth getting to know and can be found at most of the aforementioned markets. Fresh hoja santa is also difficult to come by; I bought a little packet of the dried leaves at the Yerberia Juarez, and they promptly turned to dust—hardly usable for making Oaxaca’s huevos al comal. The good news is that avocado leaves maintain their aroma and most of their uses when dried.

By the way, not all moles are made with chocolate. For those that are, Oaxaca, naturally, recommends using Oaxacan chocolate. But I’ve found that using a good-quality 100 percent chocolate bar from, say, Guittard or Eldora, works quite fine as well.

Briana Olson

Briana Olson is a writer and the editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. She lives in Albuquerque.