“That’s how it always is at a fry bread stand,” says the woman behind me. She’s referring to the slow movement of the line we’re standing in—a line stretching from the latitude of the looming movie screen all the way to the first row. “Fry bread is hard to make.”

Shivering, I glance at the truck selling barbecue and the shorter line at the stand to our right, wondering if I should have gone with the bison quesadilla. But I want fry bread, and besides, I’ve committed too much time to my place in this line to step out of it. No doubt as soon as I reached Yapopup’s stand (co-conceived and run by Ryan Rainbird Taylor, also a sous chef at the Indian Pueblo Kitchen), they’d declare that they’d sold out.

“I thought the wind would’ve died down by now,” someone else says as an icy breeze tears through. My decision to come was last minute—I had a date with the Guild in Albuquerque, but I couldn’t resist driving up to Motorama at the Downs when I learned that tonight’s one-night-only Indigenous Cinema Showcase would include a short film by MorningStar Angeline that I’ve been trying to figure out how to see. I’m dressed for a hot afternoon in the valley, not a brisk evening on the grassy high plain that is the Downs.

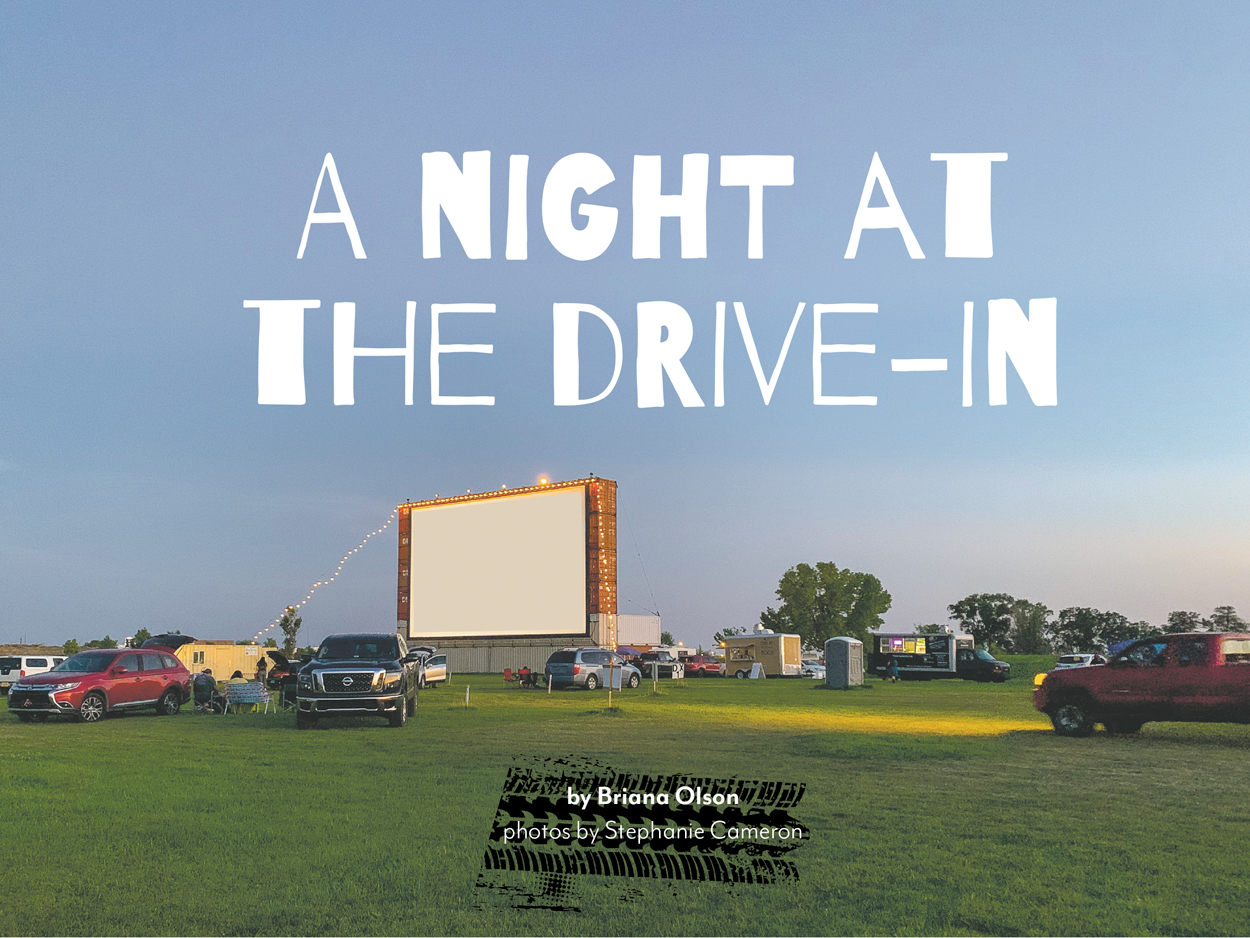

It’s a beautiful setting, and dusk is, aesthetically speaking, my favorite part of day. Arriving, I took a certain delight in driving across the lawn to reach my reserved space—the delight of forbidden things, my tires transgressing every Keep off the Grass sign I’ve ever seen.

Evone “Snowflake” Martinez’s fry bread. “I talk to my dough,” says Martinez, explaining that tender loving care is her secret ingredient. She uses only New Mexico–grown chile and homegrown pinto beans as long as the year’s crop lasts.

In line, I have the occasion to watch, over and over, as Evone “Snowflake” Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo takes a portion of dough from a bin and works it with her hands until it is supple, stretched out just enough, and then drops it in the fryer, turns it, and puts it into a tray from which her assistant immediately takes it. There is a mesmerizing rhythm to her work. It does not look hard, but I have made enough cardboard pizzas and tortillas to understand that the appearance of ease is usually illusory.

Inevitably, I recall other lines and other kinds of waiting: the line for an Academy Award–season screening in LA, lines up and down and around the block for film festivals in various cities, lines at concession stands, waiting for the ads and previews to end, for the movie to start. Waiting for the shutdowns to end, waiting to be able to steal into the dark womb of a movie theater and safely share breathing space with strangers—waiting, even still, for the crisis of the pandemic to pass. A year ago, I wondered if the crowds and chaos of such gatherings and festivals would ever happen again.

Tent Rocks still hasn’t opened back up, someone is saying, and the Indian hospital still isn’t allowing food trucks. Conversations about sewing masks slip casually into reports on previous screenings (Thunderheart was featured earlier in this monthly series, created in partnership with the American Indian Film Institute) and musings on whether to get a fry bread with a frito pie on the side.

That is my plan, but when I finally reach the front, I change my mind and order an Indian taco. Dusk has passed through me; the dancers and musicians begin to perform on a small stage in front of the screen as I move toward my car.

Yapopup birria tacos. Yapopup is the word Popay spelled backward combined with the word pop-up, and was named for the leader of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, who, like Taylor, was from the Pueblo of Ohkay Owingeh.

There are things besides the weather that I haven’t considered: that parking near the center is always preferable to parking at the edge; that I’d have to run the sound through the car (why did I assume there’d be an app for that?); that even if it had been warm enough to sit on a blanket on the grass, from the vantage of my space near the periphery, I wouldn’t have been able to see anyway.

The fry bread, despite my unexpected struggle to find a space to eat comfortably in the car, is good—thick, crispy, stout enough to carry the beans, ground beef, cheese, lettuce, and tomato.

I am still trying to figure out if I can stream the audio without leaving the car running (next time I’ll bring a portable FM radio) when Len Necefer introduces Welcome to Gwichyaa Zhee, a film by NativesOutdoors that explores intersecting concerns with Bears Ears and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Reflecting on how the caribou will be affected by opening the refuge up to drilling—not to mention the Gwichʼin people who live there and whose ties to the caribou are more intimate than I can understand or begin to describe—one of the subjects says, “In a hundred years are we gonna have all this, or is it all gonna be destroyed?”

The viewing menu is diverse in genre, moving from the documentary to animation to Yá’át’ééh Abiní, MorningStar Angeline’s stark short on apocalypse and loss. Having lately watched movies and shows where no one ever seems to eat, I’m almost taken aback by how much food courses through the first two episodes of Reservation Dogs, the FX show screening as tonight’s feature. In the opening scene, Bear and his friends steal what amounts to a truckload of chips. The man who runs a café in a gas station convenience store jokes that they eat so much catfish they might turn into one.

“Sugar, white man’s bullets,” says the town cop to one of the kids as he stands in front of a soda vending machine. “We’re still fighting chemical warfare, you’re funding their efforts.” Instead, the officer buys an energy drink. “Natural,” he says with deadpan delivery. “It’s made from energy.”

The atmosphere at the drive-in is more festival than movie theater. After each screening, people honk in applause, and when the MC introduces Reservation Dogs, listing off co-creator and director Sterlin Harjo’s awards, the audience cheers and flashes their headlights. Despite the cold, the mood is effervescent.

“I don’t care what you think,” says Willie Jack when a customer promises to return with his assessment of the meat pies she’s selling. It’s a delicious statement, not just because the comic timing is perfect, but because every cook—and likely every creator and artist—has wanted, at one time or another, to say it.

On the drive home, I tune in to a public radio broadcast on Afro jazz. They’re talking about how taste requires early education, even indoctrination. Taste is no more natural than Rockstar; it is cultivated and acquired. While Reservation Dogs entertains, it also takes giant steps in taste making, in changing the way—how, by whom, for whom—Indigenous stories are told.

“When I try something new and really love it,” Taylor of Yapopup shares later, revealing a similar taste-making aim, “I try to think how I can infuse it with Pueblo-style cooking. I do that so I can get people on my rez to try new things while also having something they’re used to.”

As for the drive-in, what ends up being special about this night is the community that’s gathered here; it’s less about the total immersion of the movie theater or the comfort of the chairs and more about the celebration.