The humble word pancake conjures feelings in my heart of comfort, home, and childhood. In what seemed like an act of magic to my young eyes, pancakes started off as an unpromising bowl of formless, pale, cold batter, but transformed in the pan to delicate, piping-hot, golden-brown rounds of pure deliciousness, ready to soak up butter and syrup and be accompanied by crisp bacon.

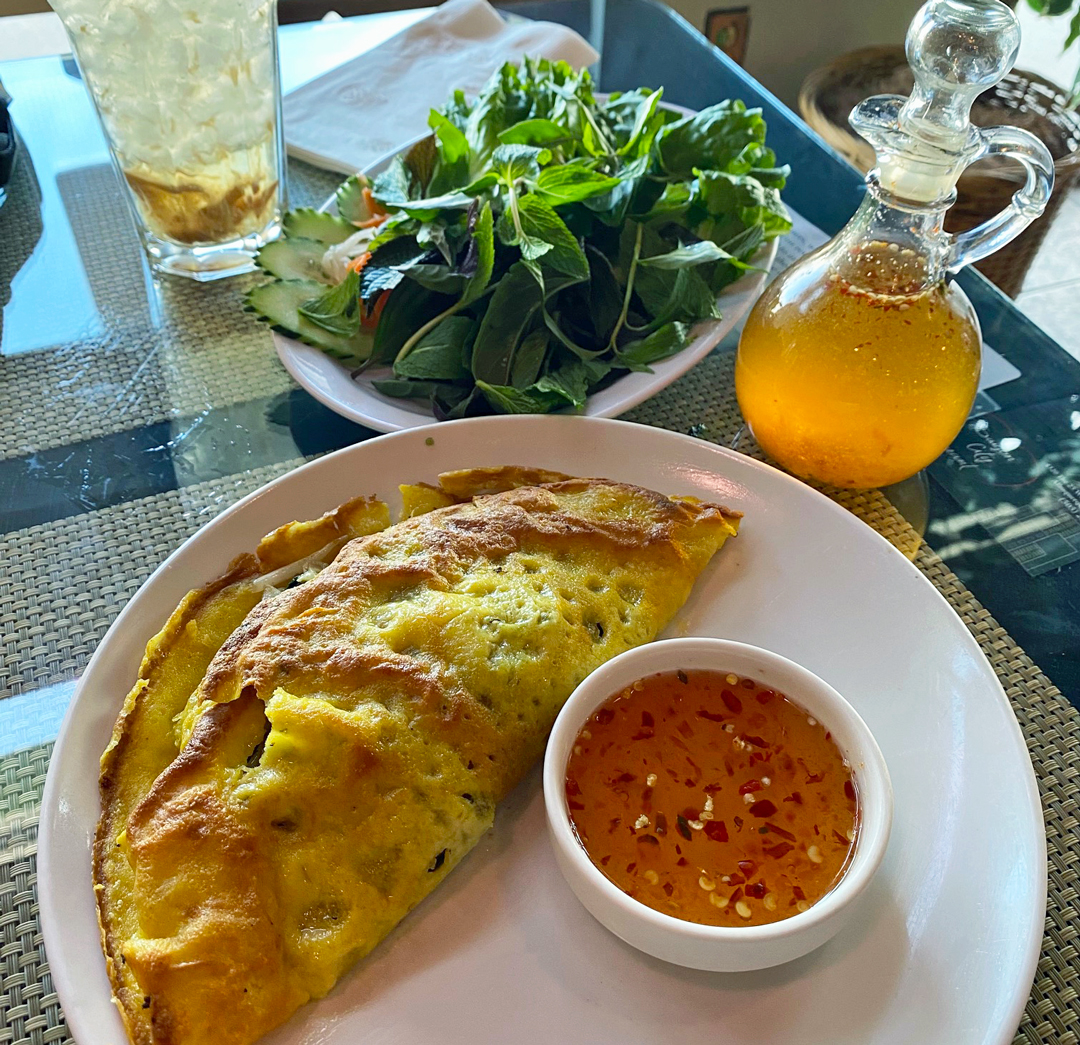

In my exploration of the Vietnamese savory rice-flour pancake known as bánh xèo, I discovered that same primal appeal—the comforting deliciousness of carbohydrate-rich batter sizzling in fat, the warm savor. In place of butter and syrup, bánh xèo come out of the pan ready to soak up the dynamic sweet-salty-fishy-sour-spicy dipping sauce nước chấm, and to be enjoyed with fresh lettuce, mustard leaves, cucumber, pickled vegetables, and fragrant herbs.

A key to understanding bánh xèo is the pronunciation: bánh refers to bread or cake, and xèo is the onomatopoeic term for the sizzling sound when the batter hits the hot fat. When saying the word xèo, listen for the sizzle in the first syllable: SSSAY-oh. In the second syllable, my server at Saigon City told me, be sure to round the oh sound fully. “If you don’t,” she said, “it sounds like the word for car tire.”

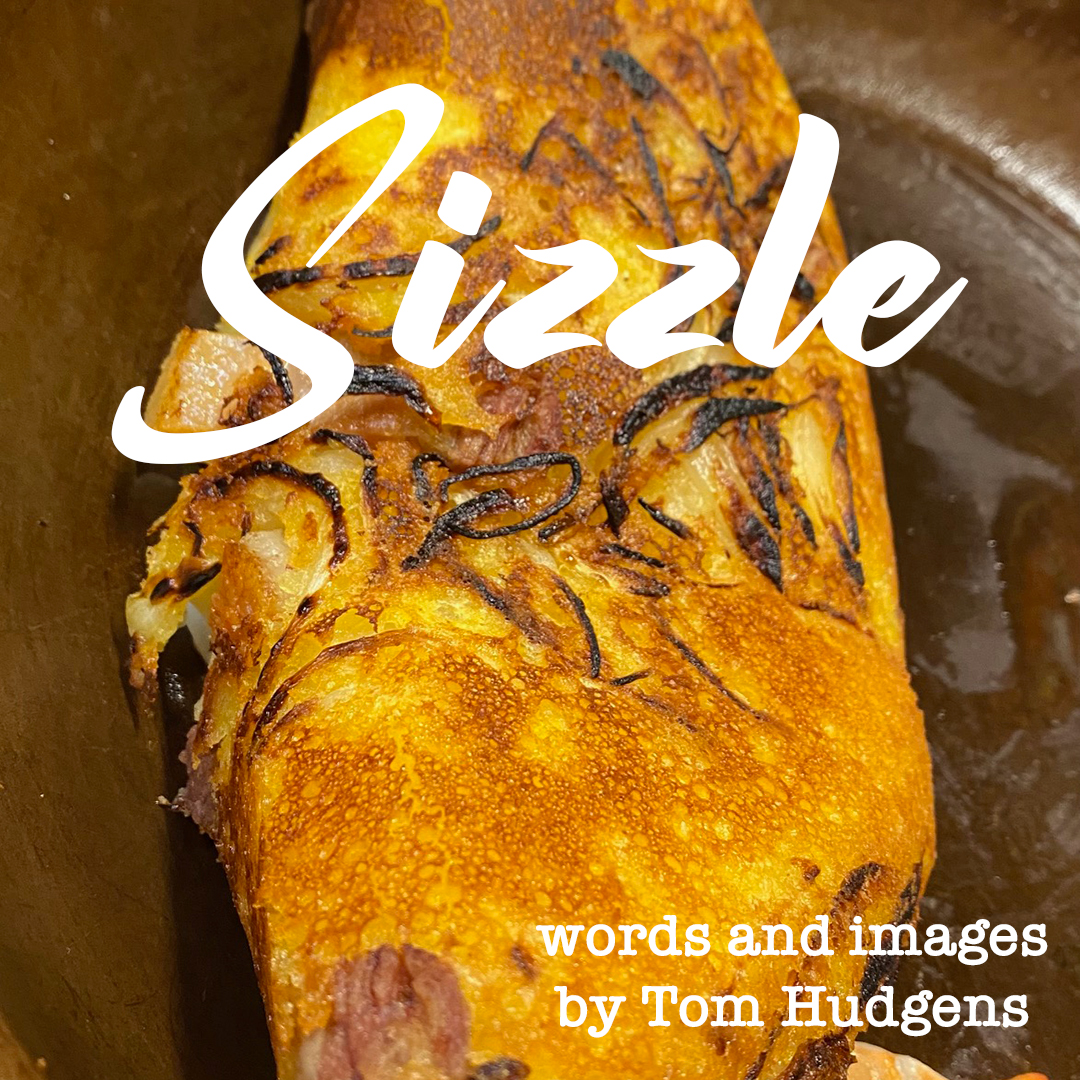

Bánh xèo batter combines rice flour, cornstarch, coconut milk, water, salt, and turmeric. The batter is poured over sizzling onions and pork, topped with bean sprouts and seasoned raw shrimp, then folded into a golden, crispy half-moon. To eat it, wedges are wrapped in a lettuce or mustard leaf, topped with vegetables and herbs, and rolled into a bundle to dip in the nước chấm. It’s a hands-on, slightly messy process, but a rewarding one when the flavors and textures—crisp pancake, rich pork and shrimp, crunchy fresh vegetables, and nước chấm—combine.

Over the course of a couple of weeks recently, I ventured out to five of Albuquerque’s Vietnamese restaurants to sample their bánh xèo. They were all delicious, and all a little different.

At Viet’s Pho on Menaul the bánh xèo has excellent flavor, and it’s served with crinkle-cut pickled carrot and daikon, cilantro, and lettuce. With a glass of sweetened coconut water that included chunks of young coconut, it was a great lunch, made only more so by the friendly, welcoming staff.

Café Da Lat on Central offers a good bánh xèo, but on their appetizers menu I found a related and rarer dish, bánh khọt, and decided to try that as well. Here, the same golden rice-flour batter is cooked in little cups, each one containing a shrimp. In the mood for a health tonic, I ordered a drink of nước rau má, also known as gotu kola or pennywort, said to be excellent for digestion. Lightly sweetened, the drink’s flavor was deep, grassy, and herbaceous.

At Basil Leaf on Eubank I found a whole assortment of bánh xèo in the crepes section of their menu, including chicken and tofu in addition to the more common pork and shrimp. My chicken bánh xèo was large and wonderfully crispy, with a pile of individual Thai basil leaves along with lettuce and pickles.

The warm and welcoming owners of May Cafe on Louisiana, in the heart of the International District, are widely respected not only for their delicious food but for their stewardship of a giant, historic Paul Bunyan–style lumberjack statue atop their building, a holdover from the days when it was a lumber store. Their bánh xèo is expertly cooked: the pork and shrimp are nicely melded with the pancake and an appealing tangle of onion sits on its firm top. It’s served with an array of fresh herbs.

Saigon City Restaurant in The Shops @25 served a spectacular plate of greens to accompany their bánh xèo that included rarer herbs such as perilla (similar to Japanese shiso), and rau ram, a type of Vietnamese cilantro. I ordered the refreshing salted lime drink as accompaniment.

After this sampling, the next step on my voyage of bánh xèo discovery was obvious: I needed to make it myself, in my own kitchen. So I stopped in to Talin Market, where I found rice flour, coconut milk, bean sprouts, excellent Red Boat brand fish sauce, Thai palm sugar, and best of all, herbs including Thai basil and perilla. Perusing various bánh xèo recipes, I learned that mustard greens are used as commonly as lettuce for a wrapper and that fattier pork, such as belly, is preferred. I used both in my recipe.

Although making bánh xèo involves preparing many elements of the meal, no one task takes very long. As the morning sun streamed into my kitchen, I washed the lettuce, greens, and herbs; marinated the shrimp; and precooked the pork. I pickled the carrot and daikon, too, though ideally that’s done a day prior to the rest of the preparation. A bit later, I made the batter and nước chấm.

As dinnertime neared, I melted fragrant coconut oil in a large skillet and scattered onions and pork belly over the bottom. Then I gave the batter a stir and poured a cupful into the skillet. Sure enough it produced a most satisfying sizzle (I swear I could almost hear the SSSAY-oh). The moment the pancakes were done, my family sat down to a bánh xèo feast. That all-important sound was evident in the crisp outer crust of the pancake, and our taste buds were simultaneously comforted by the pancake core and thrilled by the fresh, aromatic, pungent wrapping and dipping sauce.

Bánh xèo is many things: a delicious, comforting pancake that soothes the soul, a dish to order at your favorite Vietnamese restaurant beyond phở and spring rolls, and a satisfying meal to cook at home that will dazzle your guests. Perhaps best of all, it’s a window into the essence of Vietnamese cooking. To make it yourself, follow my recipe.

Tom Hudgens

Tom Hudgens is the author ofThe Deep Springs CookbookandThe Commonsense Kitchen. Earlier this year, he transitioned from a fifteen-year office career back into his original career of professional cooking, and he is now the event chef at Los Poblanos. On his last day in the office, his going-away party was catered by Coda Bakery.