It would be enough if Coda Bakery served nothing besides their renowned traditional Vietnamese bánh mì sandwiches, but they also offer superlative spring rolls, noodle bowls, salad bowls, fruit smoothies, and Vietnamese coffee, as well as an interesting array of off-menu items. It would be enough if they offered only three or four types of bánh mì, but they have no fewer than thirteen, each one distinct and delicious. It would be enough if Coda Bakery did not lavish quite the same level of care and attention that they do—for everything I order there, I always feel that in the first few bites I get my money’s worth. The remainder is a pure gift.

Coda Bakery has been my go-to lunch place in Albuquerque for most of the past three years. The food there remains as fresh, interesting, and exciting to me today as the first day I walked into their unassuming space across the parking lot from Talin Market in Albuquerque’s International District.

I recently had the pleasure of meeting the owner and chef, Uyen Nguyen, and found her fresh, bright energy to be a perfect reflection of her food. A self-proclaimed “total foodie,” she left her career as a nurse and joined forces with her father, Da, to create Coda Bakery in 2007, a time when bánh mì was still relatively unknown in New Mexico. (The name “Coda” is a reference to Da.) Nguyen taught herself to bake and, with her keen sense of taste and finely tuned palate, created the menu at Coda. Da is still her right-hand man, chief handyman, and inventor—at her urging, he came up with a device that quickly slices cucumbers for their sandwiches.

Order a Coda bánh mì, and soon you’ll be handed a hefty foot-long sandwich, cut in half and wrapped in white paper, stuffed with your chosen flavorful meat or vegetarian filling. The light, flaky house-baked bread will be spread with butter and bursting with a salad’s worth of vegetables: pickled carrot and daikon, fresh cucumber spears, thin-shaved jalapeños, and sprigs of cilantro. But a bánh mì is more than just a sandwich—it’s an encapsulation of the currents of human history. The French occupied what is today Vietnam from the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, leaving a political legacy of colonial oppression and subjugation, but also a culinary legacy of butter, coffee, cured meats, pâté, and baguettes. The Vietnamese adopted all of these foods and made them their own, taking, for example, the standard French café au lait and transforming it into rich, sweet Vietnamese coffee, or adding Vietnamese vegetables and seasonings to the basic French ham and pâté sandwich, creating the bánh mì. Today, it’s one of the world’s most celebrated “fusion” foods.

A good bánh mì is made not with a traditional chewy French baguette, but with a softer, lighter, Vietnamese version of the baguette, spread with soft butter and, sometimes, spicy mayonnaise. The meats—traditionally pâté, ham, and headcheese—are more highly seasoned than their European counterparts, and the vegetables are fresh and vibrant.

I’ve enjoyed all thirteen bánh mìs on Coda’s menu over the years. Most popular are the #6, grilled pork, marinated in three types of soy sauce, and the #5, grilled chicken. My personal favorites include the classic yet complex #1 with Vietnamese ham (called chả lụa, a sausage-like ground-pork roll), jambon (a kind of pressed ham), pork belly, liver pâte, and headcheese. (The #2 and #3 bánh mìs are simplified variations on that combination.) Nguyen sources these meats with great care, avoiding anything overly processed.

I love the #4. The tender Vietnamese pork meatballs are seasoned with a good shake of black pepper and served warm in the sandwich. The #7 features fried tofu, house made and beloved even by the tofu averse. In the more unusual #8, shredded pork and pork skin are coated with smoky, toasted rice flour and seasoned with fish sauce, creating a unique textural experience. Chao tom, #9, is perhaps the one I order most often, with its long slices of tender, delectable pork-shrimp sausage, served warm. (In Vietnamese cuisine, this same ground-shrimp mixture is often wrapped around batons of fresh peeled sugarcane and grilled.) The lemongrass beef meatball, #10, has a devoted following—the beef is finely ground and dark with soy sauce, with a wonderful lemongrass aroma.

Trứng Ơp La, #11, is made with three over-easy eggs, and happens to be my Vietnamese dentist’s favorite one. “It tastes just like the bánh mì I used to get on the streets of Saigon,” she says. Sandwich #12 and #13 both feature canned fish (another French colonial legacy): one with albacore and Korean gochujang, the other with sardines in a garlicky tomato sauce.

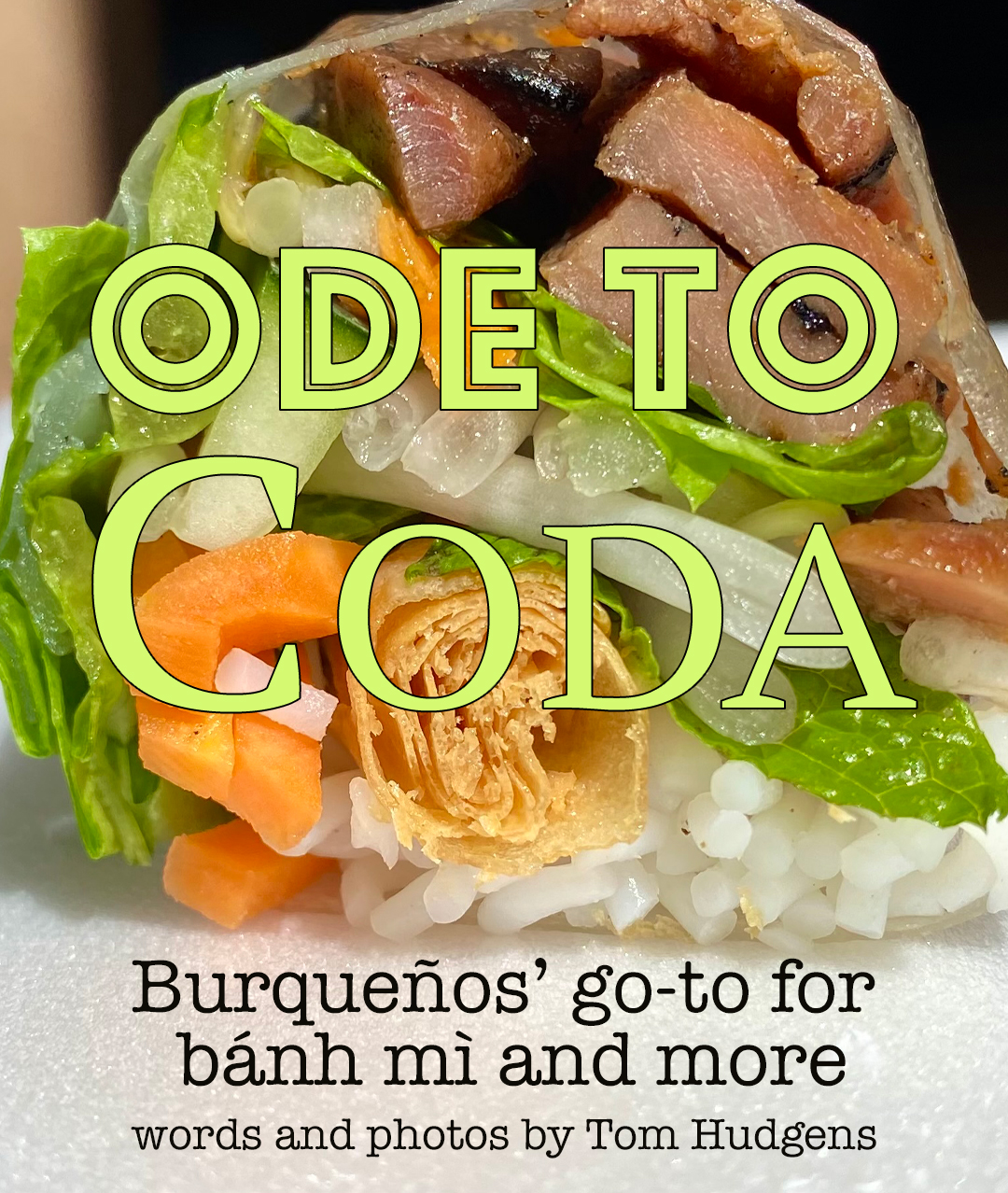

Of Coda’s spring rolls, I especially love #26. It contains the same shrimp-pork sausage as the #9 bánh mì, with springy rice noodles, lettuce leaves, and fresh mint wrapped in a rice paper roll, with the added delight of a “crunchy roll” tucked inside—a sheet of thin, phyllo-like dough rolled like a cigar and deep fried. The spring rolls come in a pair, with a dark sesame-scented peanut sauce for dipping.

I often order a smoothie with my bánh mì or spring roll. The fresh avocado is a favorite, blended with sweetened milk and ice (you can opt for coconut milk or, when available, their house-made soy milk). Sometimes I go for the tart and refreshing jackfruit smoothie, or even the durian smoothie, a rare opportunity to taste that notoriously yet fascinatingly odiferous fruit.

Many of Coda’s regulars head straight to the counter, but if you do, you’ll miss the treats stashed in the cooler by the entrance. There you’ll find half-gallon jugs of the aforementioned soy milk (with a truer soy flavor than supermarket versions), various colorful agar-based sweet desserts, shredded green mango salads to take home for dinner, or a special Vietnamese dessert drink called chè bà ba: tapioca pearls in sweetened coconut milk with chunks of sweet potato and threads of kelp.

I always like to watch Coda’s kitchen team making sandwiches in the main prep area, but you’ll see interesting off-menu offerings there too, which they make in limited quantities and sell until they run out. One of these is green pandan cake. Often called honeycomb cake for its springy, open-pored texture, pandan cake is not too sweet, showcasing the unique, grassy flavor of pandan. Other baked goods, all “fusion” foods in their own right, include the pâté chaud, a flaky pastry with a minced pork filling, and a triangular puff pastry with a filling of creamy green chile chicken, Nguyen’s nod to New Mexico’s beloved green chile chicken enchiladas. Look for fried sesame balls, which have a delectable sweet yellow mung bean filling. Perhaps best of all is the cinnamon roll, a dense, flaky, buttery spiral packed with raisins and coconut.

Among the other foods for sale at Coda are the baguettes they bake for the bánh mì, which they often slice, toast, butter, and sugar, and package for a treat akin to biscotti. You can buy whole Vietnamese ham (chả lụa) rolls and xôi lá cam, a snack of sweet purple sticky rice topped with yellow mung bean paste, coconut, and sweet/salty ground peanuts. Bánh cuon, wide sheets of rice noodle layered with sautéed shiitake mushrooms and minced pork, are packaged with fried shallots and nước chấm, the ubiquitous Vietnamese sauce that balances fish sauce, hot chiles, lime juice, and sugar. The bánh cuon is topped with slices of Vietnamese ham and a salad of bean sprouts, cucumber, cilantro, and mint. Sprinkle the fried shallots over everything and dip the noodle in the nước chấm.

Having earned the admiration of a generation of Burqueños and appearing on numerous “best of” lists, Nguyen plans a long-anticipated move to a larger space nearby, beside El Mezquite Market on San Pedro and Central. There, she’ll offer additional menu items, such as crispy fried egg rolls, and com tâm, the iconic Vietnamese “broken rice” bowl. Once considered a peasant food, com tâm, which utilizes the imperfect broken rice grains not considered suitable for export and is generously topped with pork and vegetables, has become one of southern Vietnam’s most celebrated dishes.

Nguyen’s keen sense of freshness and balance in food has clearly paid off. While we talked, we watched the flow of customers: 9-to-5ers picking up catering orders to take back to their offices, businessmen in suits, police in uniform, medical personnel in green scrubs, construction workers, all there to enjoy her delicious, thoughtfully prepared food. “For me, success isn’t about money,” she told me, “it’s about the happiness of my customers at the end of the day.”

Tom Hudgens

Tom Hudgens has followed multiple career tracks over the decades, including writing, professional cooking, and college academic support. The author of The Commonsense Kitchen and The Deep Springs Cookbook, he recently worked as Los Poblanos’ event chef, writing menus, toiling away with his team in the Campo and La Quinta kitchens, and creating delicious food for weddings, retreats, and other events. He now works as a donor engagement officer at the University of New Mexico Foundation, and cooks dinner at home from scratch almost every night.