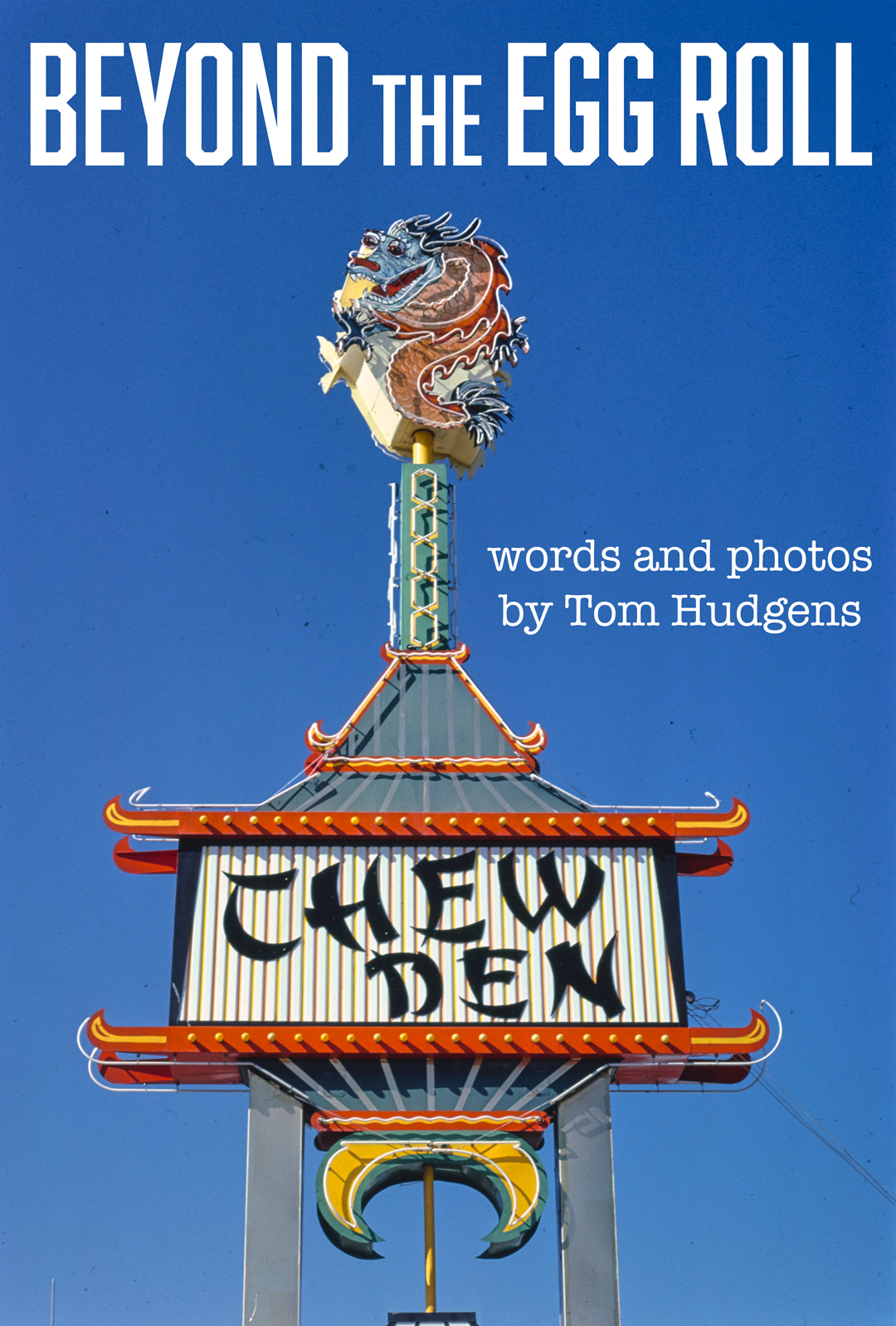

When I was very little, I loved the spectacular neon sign of Chew Den in Roswell as much as their fortune cookies, and a few years later, at New Chinatown in Albuquerque, I was equally captivated by the green-tile entrance, gracious staff, and such crispy-golden fare as egg rolls, shrimp toast, and lemon chicken. These restaurants, now long gone, were splendid examples of Chinese American cooking.

Back then, I assumed that people in China ate those same dishes. Today, though, the complexities of the story are better known: Early Chinese immigrants to the United States—mostly Cantonese-speaking, from Guangdong province in the southeast—cooked for other Chinese immigrants. Non–Chinese Americans learned to appreciate the food, and entrepreneurs tailored their menus to US tastes with enduring success. Yet Guangdong is one small part of a vast country, and Cantonese food is only one of eight distinct regional Chinese cuisines. Studying modern Chinese cooking, I’ve learned that Chinese dishes offer far more vegetables and greens, more pickled, dried, and fermented foods, more textures, more variety meats, and overall less fried, less sweet, less heavily sauced food than is typically served in Chinese American restaurants.

In my local quest to venture beyond General Tso’s chicken, egg rolls, and sweet-and-sour pork in bright red sauce, I began with ABC Chinese Restaurant on Menaul in Albuquerque. There, the usual rendition of sweet-and-sour pork appears on their main menu. But their other menu, printed on blue paper, offers a different version: the pork is more lightly breaded, and the delicious, scant sauce is less sweet and more soy forward. The next stop on a sweet-and-sour pork crawl might be Hanmi Korean-Chinese Fusion on Juan Tabo, which specializes in the cooking traditions of Chinese immigrants in Korea. Their Korean-style sweet-and-sour pork, or tangsuyuk, is also familiar, yet different: the pork is cut into strips, the breading is light, and the golden, tangy sauce contains chunks of onion, wood ear mushrooms, and pineapple. The dish is served with Korean-style sides of kimchi and pickled daikon.

Beyond the familiar lo mein and pot stickers of Chinese American cooking, people in China’s various provinces, especially in the north, consume vast arrays of noodles, and every region has a unique dumpling shape. In addition to a menu of soul-warming noodle soups, Dumpling Tea, off the Plaza in Santa Fe, serves handmade dumplings steamed or pan-fried, including vegetable dumplings with a bright, fresh filling of mushrooms, greens, and carrots in a green wrapper.

Starting about a century ago, Chinese Hui Muslims in Lanzhou, the capital city of northwestern China’s Gansu province—once an important stop on the fabled Silk Road—popularized a dish of thin, handmade noodles in a rich, spicy beef broth. Today Lanzhou hand-pulled noodles can be found all over China, and in Albuquerque too, at Iron Cafe on Central Avenue. Their excellent Lanzhou beef noodle bowl features thin, slightly irregular noodles in a deeply flavored beef broth with tender slices of braised beef and bamboo shoots, topped with slow-cooked egg, scallions, cilantro, corn, and a spoonful of umami-rich fermented mustard greens.

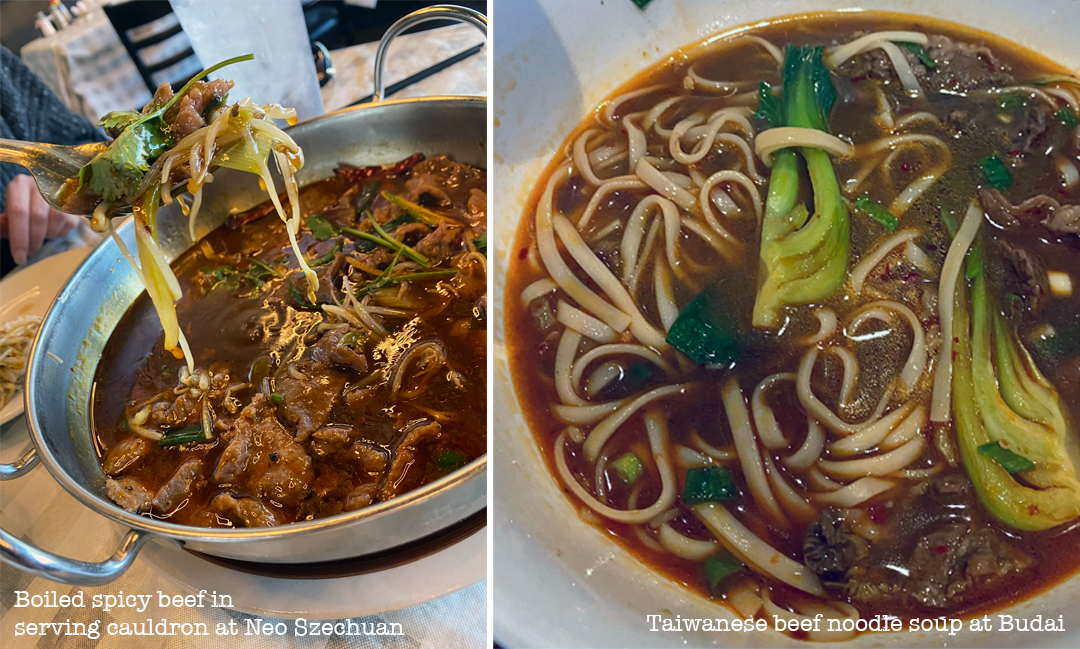

Sichuan-specific restaurants began to open in the United States in the 1970s, and they became more popular after 2005, when the USDA lifted its ban on the import of Sichuan peppercorns, a key element of Sichuan cuisine. (The peppercorns were erroneously thought to carry canker disease, potentially threatening the US citrus industry.) Unrelated to black pepper, Sichuan pepper provides a citrusy-piney flavor and a unique, mouth-numbing tingle. Paired with Sichuan’s famously hot chiles, the peppercorns tame the chiles’ heat in an exhilarating, dynamic interplay in the mouth known in Chinese as ma-la, which my friends and I happily experienced at Neo Szechuan Asian Kitchen on Montgomery in Albuquerque. Eager to sample the wide spectrum of textures found in so much of Chinese cuisine, we ordered the cold spicy beef and tripe salad: chewy beef and springy, spongy tripe, tossed with an intense ma-la dressing and refreshing cilantro. We also devoured pork-and-shrimp dumplings in a spicy Sichuan sauce. From the Chef’s Special section of the menu, we ordered the extraordinary spicy boiled beef. More than enough for four of us, the dish was a steaming cauldron of thin-sliced beef, bean sprouts, bamboo shoots, and carrots in a deep red broth bursting with numbing-hot flavor.

At local favorite Budai Gourmet Chinese, in the northeast of Albuquerque, Elsa and Hsia Fang offer Taiwanese and other Chinese specialties alongside Cantonese fare. Renowned for their hot-and-sour soup and tea-smoked duck, they also serve an array of vegetables such as pea shoots and water spinach—greens important in China but rarely prominent on Chinese American menus. When we ordered the Taiwanese beef noodle soup followed by the three-cup chicken and stir-fried sweet potato leaves, Elsa smiled and said, “You will have a perfect traditional Taiwanese dinner!” We did.

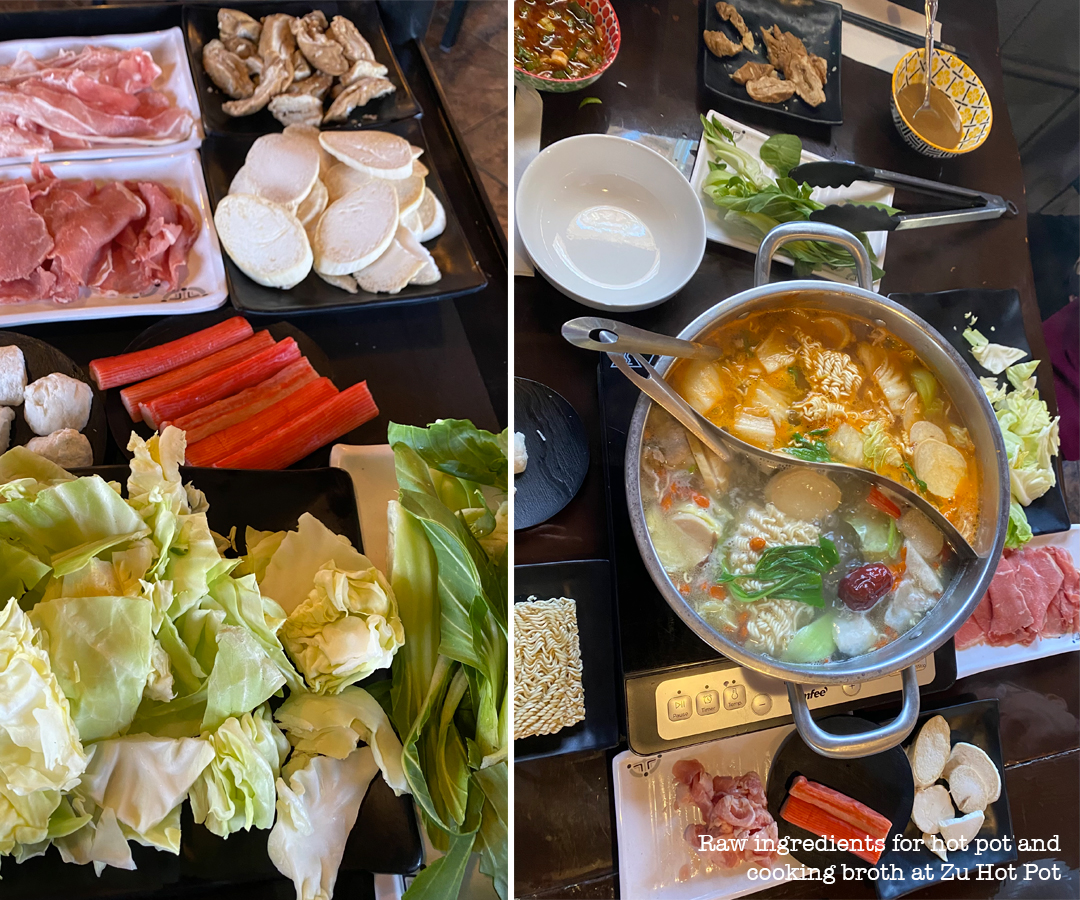

My coworkers and I met for lunch at Zu Hot Pot on Juan Tabo, where my wonderful boss, Fang, who was born and raised near Beijing (and bears no relation to the aforementioned Fang family), insisted we order the pork intestine for our hot pot, in addition to pork belly, cuttlefish balls, crab stick, cabbage, bok choy, noodles, and eryngii mushrooms. The foods came to the table on platters, to be simmered in broth on an induction burner.

An all-important element of hot pots is the dipping sauce, and Fang showed us how to concoct our own customized sauce from a bar of flavorful ingredients. I chose sesame paste, Chinese black vinegar, soy sauce, and cilantro. We boiled our meat and vegetables in the broth, fished them out with chopsticks, and dipped them in our sauce. In the end, we drank the now concentrated, enriched broth. We loved the whole experience: the progression of flavors, the fresh vegetables, the aromas, and yes, even the deep note of the pork intestine. It was a collaborative, shared adventure, and for Fang, a taste of home.

Although hardly an exhaustive education in Chinese cuisine, our tour proved to me that while the Chinese American cuisine of my childhood still abounds in New Mexico, a wealth of distinct regional dishes with an abundance of textures and flavors awaits those who seek it.

Chow Den photo courtesy of John Margolies Roadside America photograph archive (1972-2008), Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Tom Hudgens

Tom Hudgens is the author ofThe Deep Springs CookbookandThe Commonsense Kitchen. Earlier this year, he transitioned from a fifteen-year office career back into his original career of professional cooking, and he is now the event chef at Los Poblanos. On his last day in the office, his going-away party was catered by Coda Bakery.