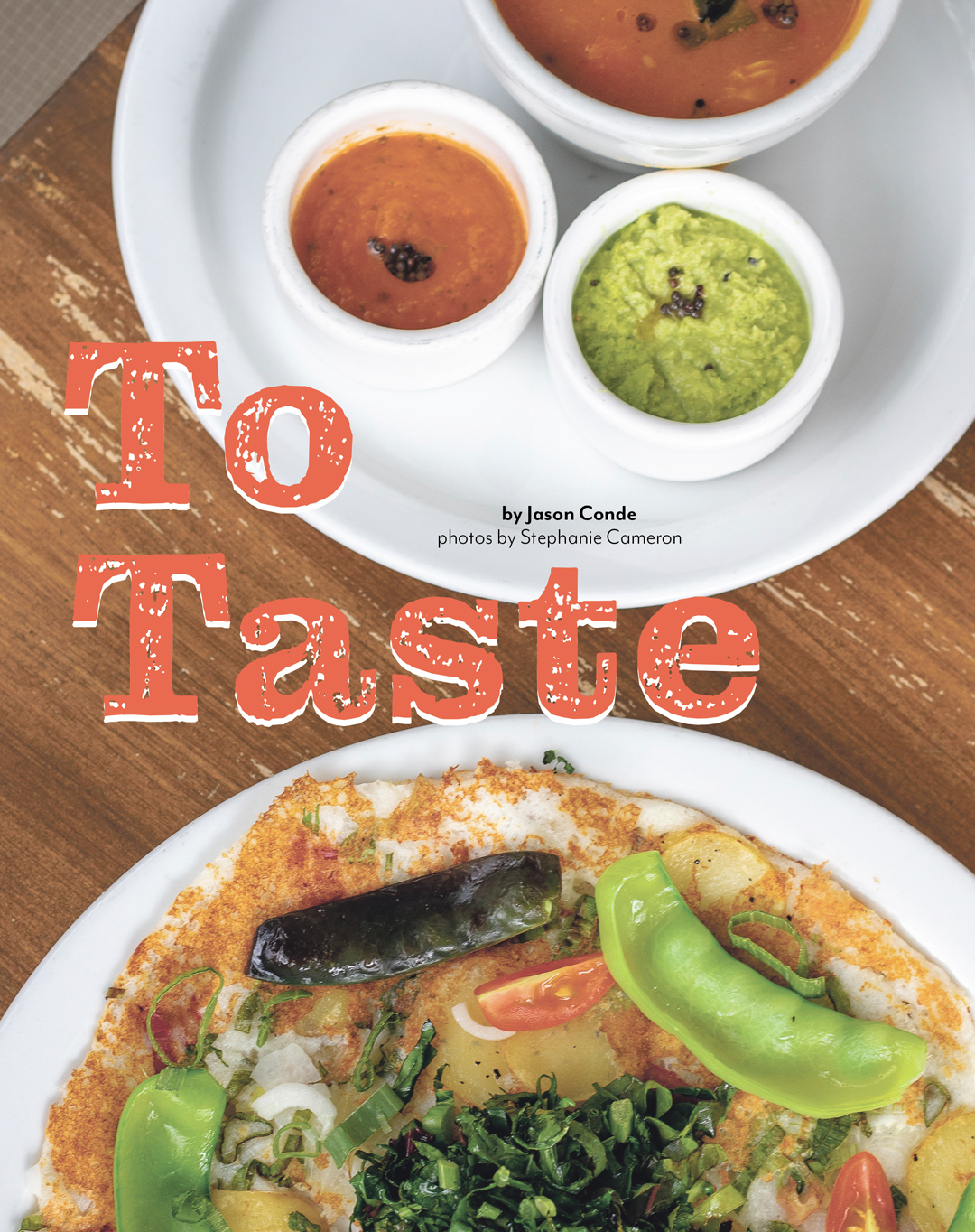

Above: Seasonal uttapam with lentil sambar, mint chutney, and tamarind chutney at Paper Dosa.

By Jason Conde

Photos by Stephanie Cameron

~

My daughter, Ramona, who turns seven this month, is not a fan of condiments. No barbecue sauce for her chicken tenders. No ketchup on her fries. When she was a toddler, she used to eat fish sticks with the same ketchup-hoisin slurry I made for myself as a kid. That felt good, like I was passing down a tradition. But now, no slurry. Her corn dog without a squiggle of mustard, her tacos lonely without their blankets of salsa. Even her pasta she wants plain, no butter or oil. “It’s good,” she says. “It’s how I like it.”

Meanwhile, I have a personal cache of Taco Bell’s Diablo Sauce packets in my glove compartment. My mom airmails me jars of bagoong that I eat with apple slices and cold rice. And with supply-chain issues affecting food availability, I’ve contemplated taking a bottle of sriracha from a nearby restaurant’s condiment caddy. So Ramona’s aversion to condiments strikes me as odd, though probably temporary—it will eventually pass, like each one of her birthdays. Still, I’m befuddled that she doesn’t enjoy the sauces that bring so much flavor, texture, and nutrients to other foods, and I’m reminded of a man I knew at a soup kitchen in Texas. “I’m here for a cheeseburger,” the man said after I pointed to the condiment bar I’d set up. “Not a cheese and crap burger.”

~

At the Santarepa Cafe in Santa Fe, where they serve Venezuelan arepas, empanadas, cachapas, and patacones with squeeze bottles of chimichurri and garlic mayo, I explained the different sauces to Ramona, who listened to me talk about how condiments add colors and flavors to food as well as offer the opportunity to develop our personal tastes. I squeezed some of the air from the bottles toward our noses and smelled tempered parsley, cilantro, vinegar, and the rich aroma of fresh garlic.

But no sauce for her yuca fries, her tequeño, or her carne mechada arepa. I tried plain bites. “See,” she said. “It’s good like that.” She was right. The yuca fries were crunchy, with a fluffy interior. The tequeño had a buttery layer of dough fried around a warm stick of queso asadero. And the arepa, with its contrast between crisp and soft, was a perfect backdrop for the shredded carne mechada.

Then I ate bites with smears of each sauce. The clean flavors of cilantro and parsley with the airy, emulsified feel of oil and vinegar and the smooth garlic sauce layered creamy textures and bright flavors beyond each dish itself. “Sure you don’t want to try the sauces?” I asked.

“I’m sure,” she said, nibbling on a yuca fry.

Above: Kale and onion pakora with eggplant chutney; Chennai chicken with raita; Chettinad lamb curry and lamb keema dosa served with sambar and chutneys. All dishes from Paper Dosa.

~

In her book Indian Cooking, Madhur Jaffrey explains the roles of Indian chutneys and yogurt raitas. “Their function,” she writes, “apart from teasing the palate with their sharp contrasts of sweet, sour, hot, and salty flavors, is to balance out the meal with added protein and vitamins.” I tried to convey this sentiment at Paper Dosa—a South Indian restaurant in Santa Fe specializing in dosas with curry masalas, lentil sambar, and various chutneys—when Ramona asked about the raita served with her Chennai chicken. I told her it would cool the chicken’s spice. “Like milk,” she said, but even after experiencing its cooling effect off a fork tine, she still used the raita sparingly.

Marinated in yogurt and spices, the fried chicken pulled apart easily and was full of flavor and texture on its own, but the raita added a tart contrast to the ground cardamom and cloves caramelized over each tender morsel. The wafer-thin dosas, made with a fermented batter of lentils and rice, came to life with mint chutney and savory lamb keema. A jammy tamarind chutney added a sweet-and-sour layer to the woody nuttiness of our mushroom uttapam, and bites of our paneer-and-pea-stuffed dosa dipped in the lentil sambar and topped with tomato chutney brought about warm recollections of grilled cheese and tomato soup.

“They taste like vegetables,” Ramona said after trying each chutney, and I realized she is developing her associations with the foods I hope she will appreciate. And through her young sense of taste and smell, I recalled standing by the stove with my mom, waiting for a piece of plain fried tofu to eat hot and without its sawsawan dip of crushed garlic and cane vinegar, my own hesitance to the charm of condiments now only a memory.

Bulgogi, bibimbap, and gau mandu at A-Ri-Rang Oriental Market.

~

I know better than to encourage Ramona to try the kimchi, any of the other vegetable banchan, or the fermented sauces and pastes that complement a Korean meal. She likes for all of that to be as far away from her on the table as possible, but she loves bulgogi and dumplings—and a good market restaurant.

Inside A-Ri-Rang Oriental Market in Albuquerque, a four-table restaurant serves Korean-style barbecue, bibimbap, noodles, and jjigae, along with dumplings, savory pancakes, and even croaker. Our thinly sliced beef bulgogi, with flavors of soy sauce, garlic, and pear, was panfried with carrots and onion, and plated on a sizzling cast-iron platter that released the smoky scent of seared meat. The panfried mandu dumplings were filled with minced pork and aromatic scallions and served with a tangy mix of soy sauce, garlic, ginger, chile, and vinegar. House-made kimchi, spicy radish, and pickled seaweed banchan rounded out our meal, adding a bold crunch, bright green and red hues, and a briny sweetness.

Ramona ate mouthfuls of beef and rice between dumplings but left the banchan to me. I didn’t try to convince her of the balance of flavor, texture, color, and temperature Korean meals aspire toward. I’m optimistic that her palate will one day enjoy the harmony of pickled radish and sweet bulgogi over steaming white rice. I was content to be together at the table, watching Ramona dip the end of a chopstick in soy sauce and scribble what little sauce adhered across a dumpling.

Jason Conde

Jason Condeis a writer and educator. He lives in Las Vegas, New Mexico, with his partner and their daughter.