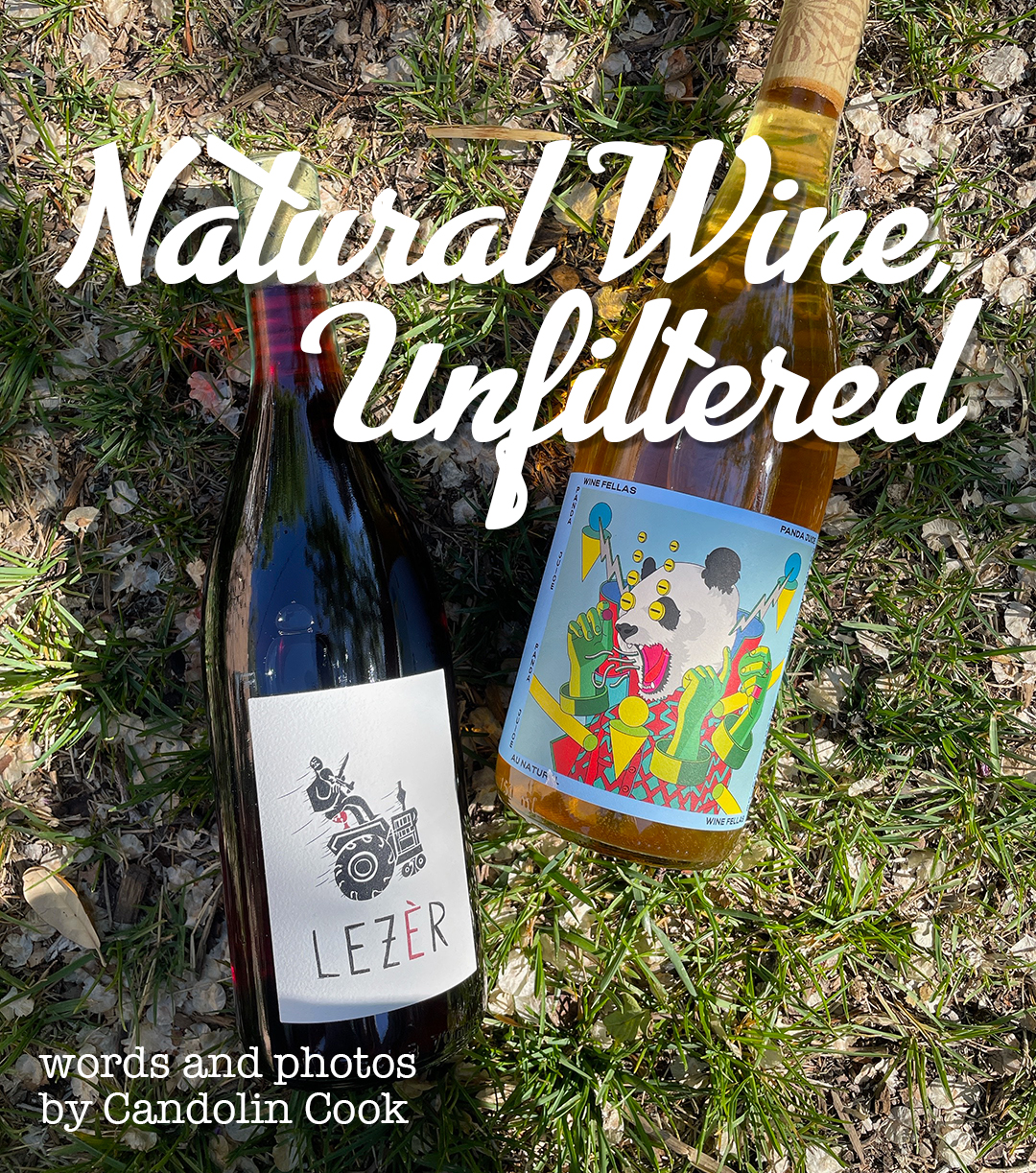

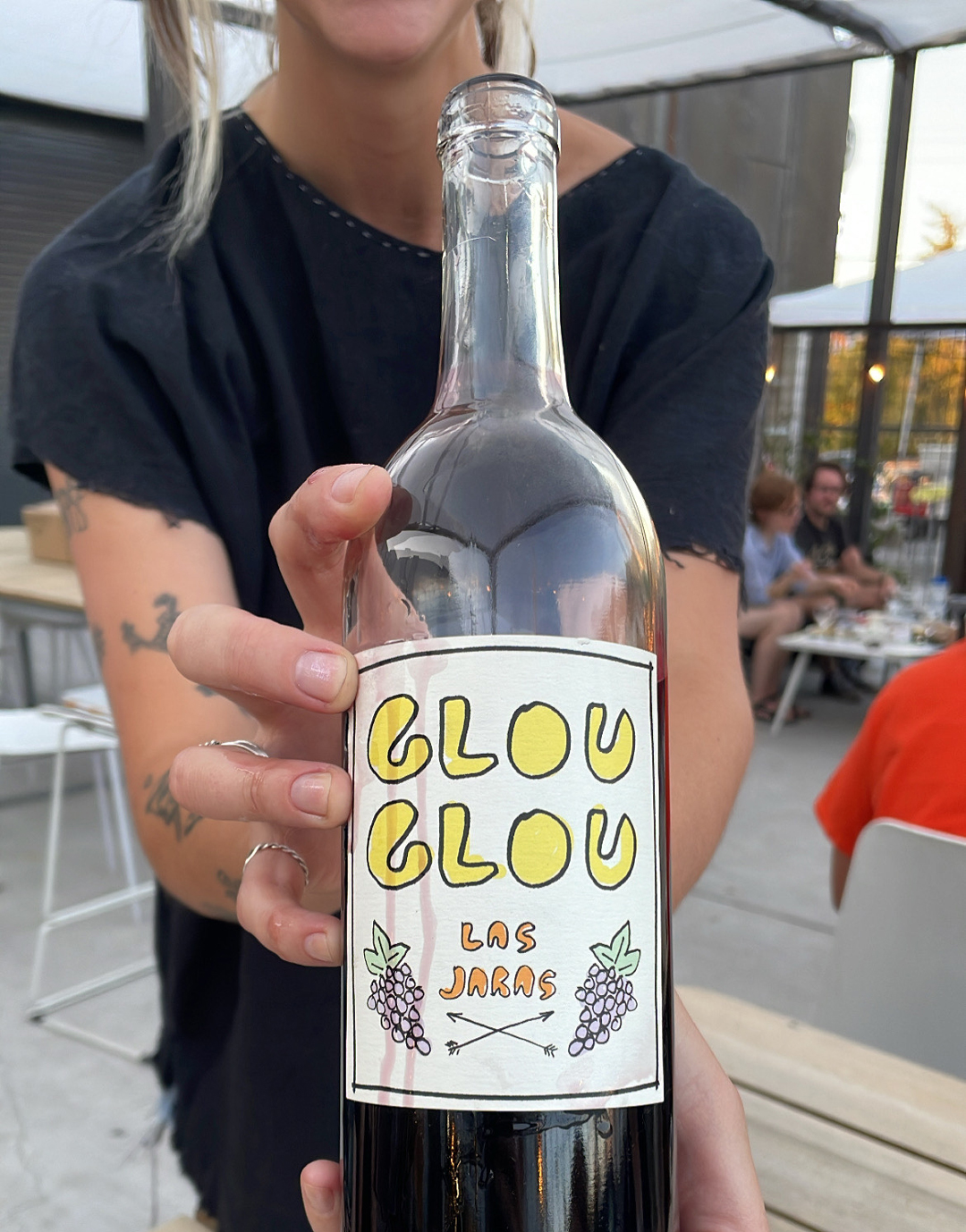

“Are you a wine daddy?” asked the DJ at a trendy club in East Hollywood. “Am I a what?” replied the chicly dressed thirty-something guy next to him. “A WINE DADDY,” he said louder, over the music. “Are you into natural wines?” A look of understanding and excitement washed over the man’s face: “Oh yeah, of course!” I continued to eavesdrop on this conversation for the next several minutes as the two shared recommendations for local “natty” wine bars and their favorite producers of pét-nats (sparkling, partially fermented natural wines) and glou-glous (a French onomatopoeia for “glug-glug,” signifying a highly drinkable, juice-like natural wine). The exchange was not unusual, I soon discovered on this recent visit to Los Angeles. It seemed that everyone (at least everyone under a certain age and living in hip neighborhoods like Silver Lake) was drinking, discussing, and gushing about their love of natural wine.

Nationally and globally, the popularity of natural wines has grown exponentially in the last five years. Experts cite the pandemic as one reason for that growth, as supply chain problems and COVID concerns saw more consumers clamoring for local, small-batch, and “healthier” products. Finding data to quantify sales is difficult, however, because there is no universally accepted definition for what natural wine is. In the simplest and most agreed-upon terms, natural wines are made using organic, biodynamic, or sustainable practices; forgo interventions, such as filtration; are fermented with native yeast and bacteria; and are mostly additive free, i.e., contain no or low sulfites, sugars, commercial yeasts, dyes, or animal products, like egg whites and isinglass—a fish bladder derivative often used as a fining agent in conventional wine production. (The FDA has approved sixty additives vintners may use without listing them on the label.) TL;DR, natural winemakers subscribe to a “nothing added, nothing taken away” approach. The impreciseness of this process may result in “imperfections,” but it also leads to interesting flavors, colors, and consistencies. (Think funky or juicy, orange or purple, cloudy and/or effervescent.)

Perhaps an easier metric to gauge natural wine’s ascendancy is its prevalence in modern food culture, especially that geared toward millennials and Gen Zers. These drinkers gravitate to natty wines, in part, because they are seen as humble, approachable, and fun—a departure from older, stuffier wine culture. Marketing for natural wines relies less on touting regions or master vintners and more on their irreverent names and colorful labels, which are often humorous, whimsical, and artistic. The bottles’ visual appeal lends itself to prominent displays in restaurants and bars, as well as on Instagram and TikTok, where influencers’ posts send a somewhat contradictory message: “Natty wine is for everyone” but “IYKYK.” For those indeed in the know, being a natural wine fan provides a certain cachet among the food-as-fashion crowd. These wines have become so ubiquitous that, according to a recent Bon Appétit article, they may already be losing their “cool factor.” Nevertheless, the piece explains that the demand for “millennial wine” isn’t going anywhere, quoting one importer as saying, “If you’re opening a restaurant in New York City without a natural wine list right now, it’s like, what are we even talking about?”

Scene from a California Natural Wine tasting event at Little Bear Coffee in Nob Hill, Albuquerque.

Meanwhile, in New Mexico, natural wine has yet to saturate the local market. However, its consumption—conspicuous and otherwise—is on the rise. In just the past year, three natural wine bars have opened in Santa Fe and Taos (La Mama, Copita, and Corner Office) and, in Albuquerque, Nob Hill coffee shop Little Bear expanded its hours to become an evening natural wine destination. Several liquor stores, such as Kokoman (Pojoaque), Kelly Liquors Solana (Santa Fe), and Jubilation (Albuquerque), have finally caught on that “organic” and “natural” wines are not necessarily the same thing, and are stocking the latter with more regularity and intention. And, from Campo to Tesuque Village Market, more restaurant wine lists now offer an assortment of well-curated low-intervention selections. Much of the increase in both supply and demand is thanks to a small but passionate cadre of locally based natural wine distributors, sales reps, and retailers. I recently called on two of them, Paul Greenhaw and Martha Aguilar of PM Wine Distribution, to get a better understanding of natural wine and its growing appeal in New Mexico.

Paul Greenhaw and Martha Aguilar, owners of PM Wine Distribution.

Greenhaw’s and Aguilar’s love of natural wine began during the aughts while they were living in Brooklyn, which, at the time, was the epicenter of the natural wine movement in the United States. After the couple moved to Taos in 2017, Greenhaw started working at the Cellar wine shop and Aguilar took a sales job with a local Budweiser distributor. While she quickly surmised that the gig was not for her, she learned the ins and outs of alcohol distribution and got to know the buyers at local restaurants. As she and Greenhaw reevaluated what they wanted to do professionally, they asked themselves what they were passionate about and where they could find a niche in the local economy.

In 2018, they launched PM Wine Distribution with a mission to bring wines from small producers using minimal interventions to New Mexico. However, breaking into a regional market largely unfamiliar with their product was difficult. “From day one, education was a big part of the business,” says Aguilar, who still works to dispel popular misconceptions about natural wine. (Unfiltered wines are not unclean, they don’t all taste like kombucha, and they’re not just for vegans and hippies.) “People hear ‘natural’ and they think of ‘no sugar added’ wines marketed to yoga moms,” says Greenhaw, who prefers the terms “raw” or “traditional” wine. “‘Natural’ wine is not new or [gimmicky]; it predates industrialized commercial wines by thousands of years.”

Greenhaw and Aguilar say it wasn’t until the pandemic, when an influx of younger people from bigger cities like San Francisco relocated to northern New Mexico, that their business really took off. “They moved here knowing the makers and [styles] and were not shy about demanding certain wines.” Several even reached out to them about opening up natural wine shops in Santa Fe but were deterred because of New Mexico’s strict alcohol sales regulations and exorbitant package licensing fees. “We’re talking half a million dollars to open a liquor store here,” says Greenhaw. “If there’s a political call to action, it’s to push the restructure and redistribution of these licenses. There’s a lot of room for [this industry] to grow.”

Wavy Wines’ “Super Californian” Sangiovese blend, San Benito County, CA, 2022.

Many natural reds are best served slightly chilled.

Beyond the demand from California transplants, Greenhaw and Aguilar are now seeing more excitement for natural wines among longtime residents. They credit New Mexico’s robust craft beer scene and mezcal market for instilling an affinity for and knowledge of artisanal beverages. And—contrary to this article’s earlier suggestion that natty wine’s popularity is driven by aesthetics—they believe low-intervention wines actually resonate with younger fans for some of the same reasons the Slow Food movement does. “I think [the younger] generation is bored of the wines their parents drank and tired of phony shit,” says Greenhaw. “They want real bread, real cheese, real wine,” he says, suggesting food and drink is at its most authentic and alive when it’s left at its essential ingredients. Aguilar adds, “Maybe they aren’t even conscious that’s what they’re doing but [by buying sustainably grown wines] they’re saying ‘fuck you’ to bigger [industrial-ag] entities.” After personally polling a couple dozen wine drinkers here in New Mexico (via Instagram, of course), I discovered that, indeed, transparency and a “less processed” approach were at the top of their reasons for purchasing natural wines—though they did admit the pretty labels also had something to do with it.

Orange wine of the day at Bar Campo. Orange wines, also known as skin-contact wines,

are made from white wine grapes fermented with their skins.

One last prevalent (and debatable) reason many are opting for natural wine is the belief that they cause fewer or less-intense hangovers. Many drinkers, including yours truly, are convinced that they feel better the morning after consuming natural wine than they do conventional. Some say this is due to the absence of pesticides and the lower presence of sugar and sulfites, which are used as a preservative and stabilizer. Others contend that raw wine is gut friendly because its microbial content has not been filtered out. Perhaps the most likely explanation is that many natural wine varieties have lower ABV levels, which could make that fizzy piquette (technically, a natty wine byproduct made from grape pomace) easier to process. Despite anecdotal affirmations, the science is still out on these claims, and if you drink enough of any alcohol, you will likely regret it.

However, according to Aguilar and Greenhaw, natural wine might have other benefits to body and mind. “We didn’t get into [raw wine] for health reasons,” Aguilar admits, “but there is an aliveness and vitality to biodynamic wines. No one talks about ‘How does wine make you feel?’ but we should. It’s a food product and it affects you. Sometimes, that might just mean ‘It makes me happy.’” Greenhaw agrees and says that when you overprocess and overanalyze wines, it “deadens” and “strips the joy” out of them. “With rustic wines, you keep the soul of the wine. It’s time for New Mexico to experience that.”

Selection from the California Natural Wine tasting event at Little Bear Coffee.

Candolin Cook

Candolin Cook is a historian, writer, editor, and former co-editor ofedible New Mexico.She recently received her doctorate in history from the University of New Mexico and is working on her first book.