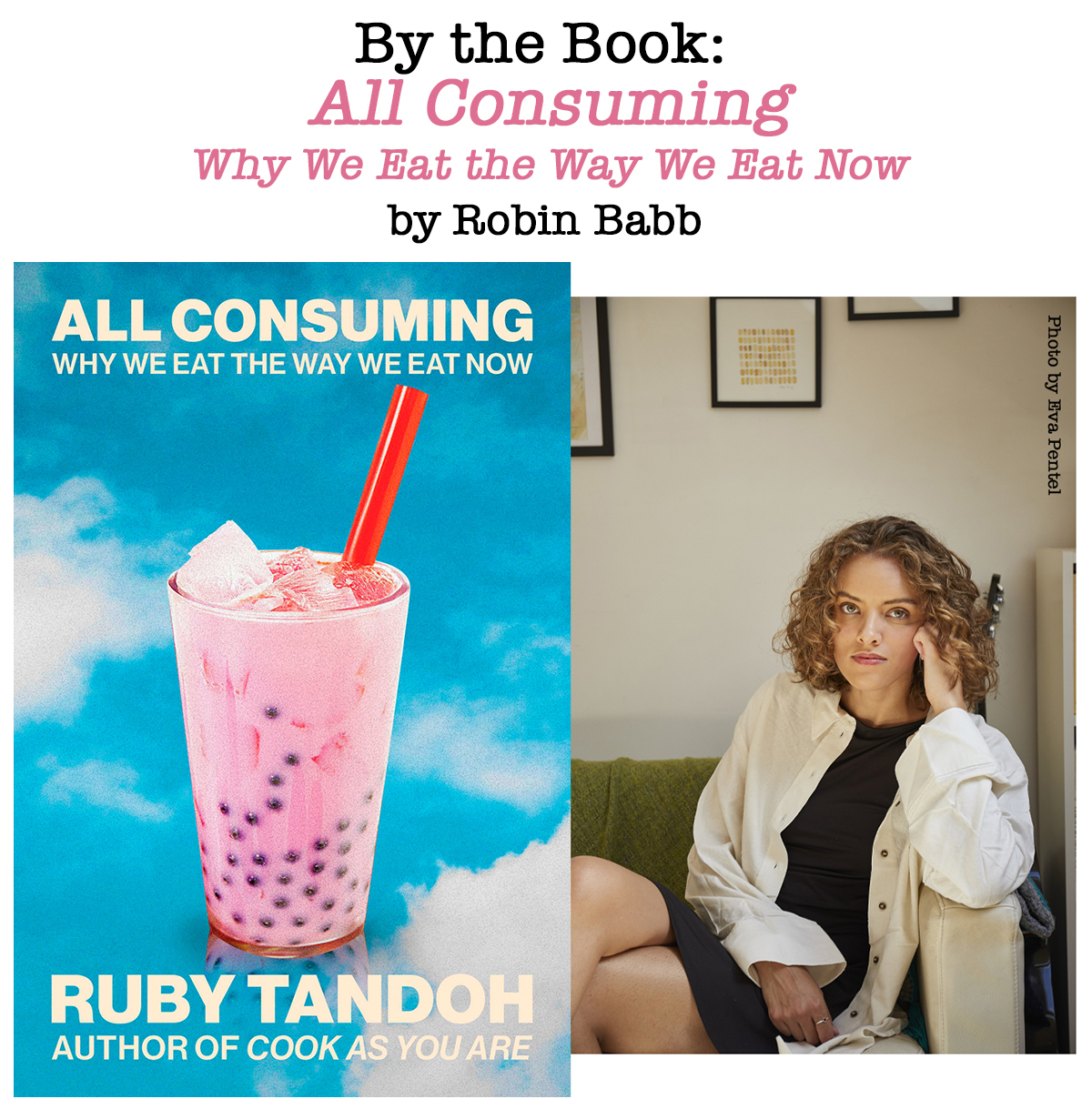

All Consuming: Why We Eat the Way We Eat Now

by Ruby Tandoh

I admit it: I am downright envious of Ruby Tandoh for how phenomenal of a writer she is. Her book All Consuming: Why We Eat the Way We Eat Now is about contemporary food trends and their roots in history—but I believe I could just as enthusiastically read her takes on any number of subjects I have little to no preexisting interest in. The conversational charm of her voice makes the material so engrossing that you can’t help but be interested right alongside her. That said, if you do happen to be interested in, say, how viral influencers became such a crucial component of restaurant marketing, how American supermarkets aided the collapse of the Soviet Union, or why bubble tea took off in the West in such a big way in the last decade, then you’re in for a real treat, because All Consuming will explain it all to you in an engaging and informal way, backed up with solid reporting and Tandoh’s years of experience working in kitchens and in food media.

If you recognize the name, it may be because Tandoh was a finalist in The Great British Bake Off back in 2013, or because of her previous books Eat Up!, Crumb, Flavour, and Cook As You Are, or because of her many contributions to various magazines over the years—she has a hell of a CV. She is also, as you will grasp within the first ten pages of the book, terminally online, as the kids say. Her vocabulary is Gen Z slangy, laced with dry British wit, and her style could, perhaps, be alienating to some readers. To me, it seemed appropriate for writing about viral recipe videos, the rise (and Midwesternization) of Allrecipes, automats, pizza vending machines, and vapid wellness trends.

Every chapter—each of which could be read as a stand-alone essay—takes a specific subject in the modern food world, then dives back in time to find its roots and trace its evolution, uncovering the people and places who helped make it what it is now. In the chapter about the origins of modern food criticism, Tandoh discusses Duncan Hines’s Adventures in Good Eating as well as Victor Hugo Green’s The Negro Motorist Green Book, two 1940s-era serials written by traveling hobbyists, each with a very different purpose and audience in mind. When she circles back around to the twenty-first-century version of food critic she opened the chapter with—a spectrum in which she includes figures as disparate as Jonathan Gold, longtime food critic at the Los Angeles Times, and Keith Lee, the viral MMA-fighter-turned-TikTok-food-critic known for his 1–10 rating system—she effectively places our modern culture wars in their historic context, while reminding you that, differences aside, all of these people are (or were) trying to make money. The legacy media food critics of the world might face accusations of elitism or good taste gatekeeping, while the Keith Lees get called hacks or sellouts, but they are both, essentially, doing the job of food critic. And, as Tandoh says, “When people don’t want to call stars like Keith Lee critics, sometimes they’ll call them influencers. Of course, nobody cares about the difference except critics themselves.”

Importantly, Tandoh never insinuates that she’s somehow above the madness and the marketing. Peppered throughout the histories are some of her own anecdotes of falling for stupid trends and being manipulated by algorithms, which, rather than subtracting from any sense of expertise, just make her seem honest. “As much as I like to complain about queueing and viral mash-ups and circular hype,” goes one such admission, “the truth is that a person can’t ironically queue. I had to admit this to myself a few months ago, voluntarily in line for the worst sandwich I have ever had, designed by a man I don’t trust, for which I paid £16. You’re either in line, or you’re not. Mild humiliation kink is one of the big drivers of restaurant culture right now.” There’s no such thing as being immune to hype, and pretending at it just makes you sound either holier-than-thou or remarkably naive.

Still, it’s easy to be nothing but cynical about food culture these days: the paid influencers and algorithmically addictive food ASMR videos, the flash-in-the-pan restaurants that get famous from one well-timed Instagram post. But, as All Consuming proves, food culture has always been chaotic, and has always swerved wildly between elitist and democratic—it’s often not even clear which is which. It’s good to make an attempt to see it all soberly, of course: to know your farmer and care about how your consumer choices affect the environment. But I’d argue that it’s equally important to remember that you’re as much a subject to the tides of culture and trend as anybody else—whether you’re a food critic for the New York Times or just looking for a nice place to take your out-of-town guests for dinner. Every once in a while, it’s true, the drink/restaurant/recipe that everyone is posting about actually turns out to be good.

Did you miss it?

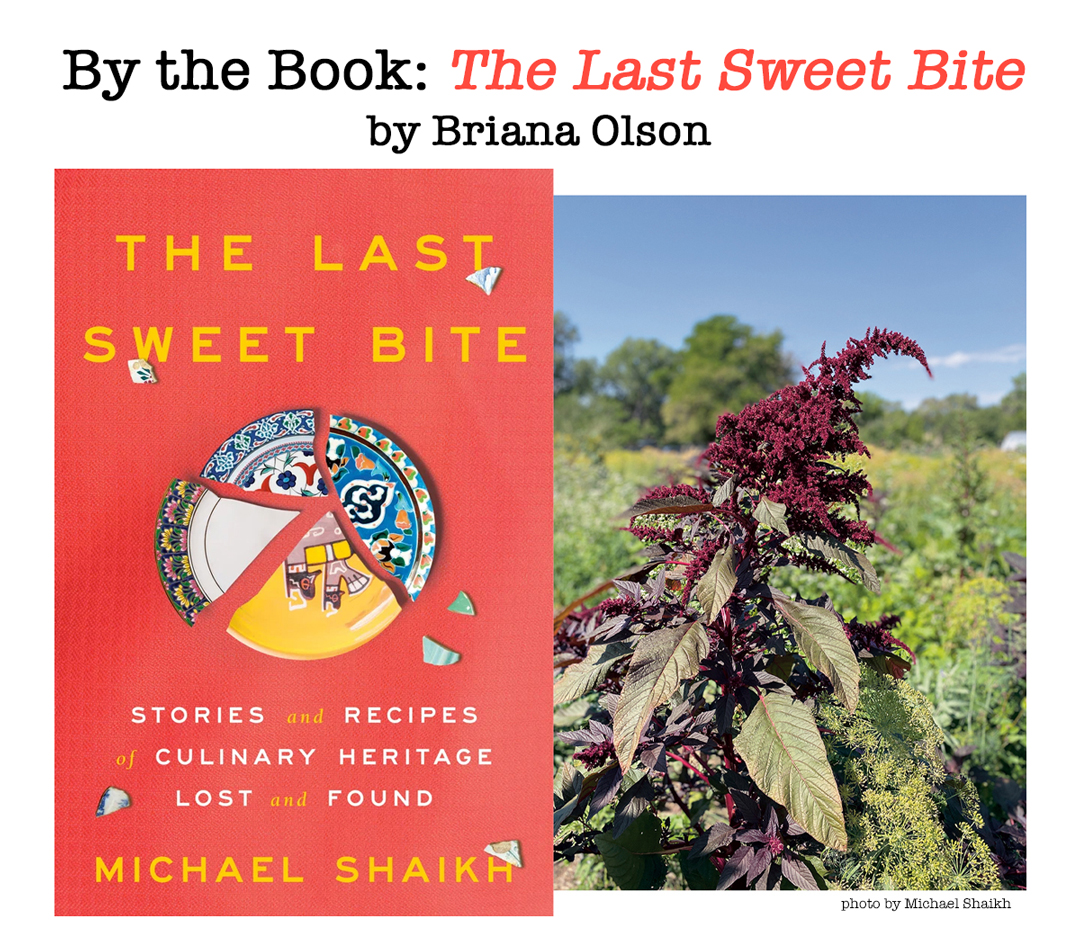

Earlier this year, we reviewed another recent book that digs into the “why” of twenty-first century ways of eating. In The Last Sweet Bite, Michael Shaikh explores how culinary traditions are altered by warfare and violence—and how the people who live by those traditions are trying to hold on. This might not exactly be a cookbook, but, Briana Olson reports, its recipe for goru ghuso, Rohingya beef curry, is a keeper.

Robin Babb

Robin Babb is the associate editor of edible New Mexico and The Bite. She is an MFA student in creative writing at the University of New Mexico and lives in Albuquerque with a cat named Chicken and a dog named Birdie.