FRY BREAD MEMORIES

AND OTHER STORIES

by Jaclyn Roessel

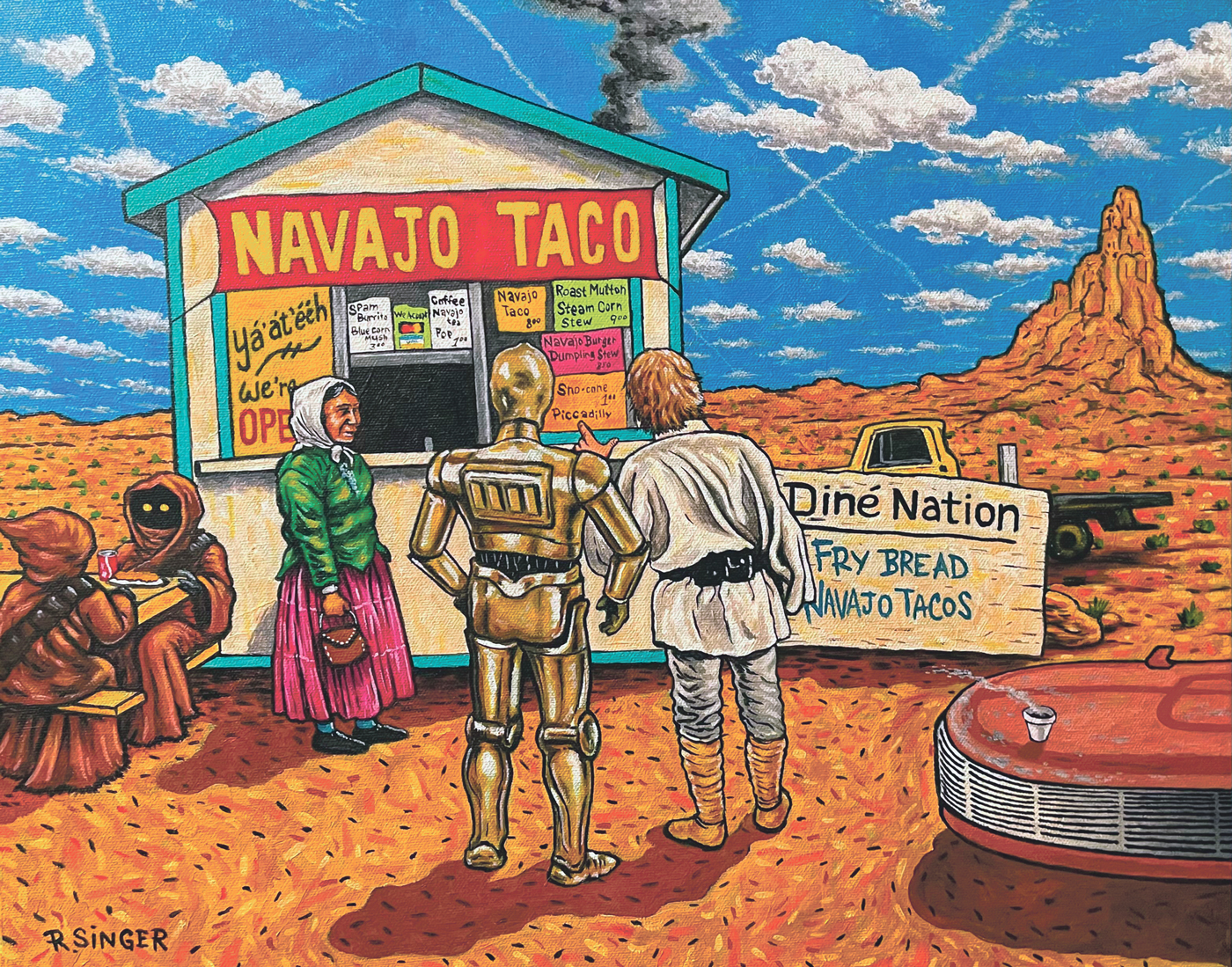

art by Ryan Singer

photos by Ungelbah Dávila-Shivers

T here are two recurring debates my partner and I have, often in jest and sometimes, depending on our level of hunger-induced irritability, in seriousness. The first is who held on to whose hand the longest when we first met. The second, and maybe just a little more contentious, is the great Navajo taco vs. Indian taco debate. “Why is it,” my Pueblo partner is always curious, “that Navajos tend to add their name to things—Navajo taco, Navajo burger, and Navajo tea?” I usually laugh and then sigh as we go back and forth, debating the history and how much the name is really an indication of the place it’s made. This continues until the conversation ends with wistful declarations that fry bread sounds like a really good snack.

Growing up on my reservation in northern Arizona, on special occasions my mom would let us pick the menu. It was not unusual for my siblings and I to request our grandma’s Navajo tacos for our celebratory nosh. Since our grandma lived ninety minutes away, this choice required some coordination. We would wait eagerly as our mom called our grandma to give her the details of the occasion. Then she would signal to her mom that we had a question for her. I recall being nervous every time I took the phone, always unsure if she would agree. But each time we asked her, she would laugh and offer a playful sigh before telling us she’d make the dough before leaving the house so she could fry the bread just before the party, ensuring the golden delights would still be warm when our guests made their tacos.

The heart of a Navajo (or Indian) taco is the fry bread. Drizzled over the bread are slow-cooked pinto beans, sometimes made chili style, vegetarian or with beef. Depending on familial preference, the usual toppings include lettuce, cheese, tomatoes, and onions. Those are the basics. There are places and individuals that use olives, salsa, green chile, and various meats to add some flair and heat.

But the foundation of this dish is fry bread. It is the ingredient that will make or break a good taco, literally. The optimal effect is when the beans can soak into the bread and not make it so soggy that it tears open when folded into a taco for that first bite.

Fry bread is a simple food. Flour, water, a little bit of salt, and—with some practice and technique—you have the makings for a decent batch of dough, ready to be fried. But the history is not quite so simple; the initial demand for fry bread was created during, and as a result of, devastating change in Native communities.

Despite its notoriety as an Indigenous food, the fare is not indigenous to North America. Wheat flour was part of the rations provided to the Native people who were imprisoned at forts and reservations around the country during the Indian Wars of the 1800s. In the case of the Navajos, flour was distributed while we were imprisoned by the US government at Hwee∤dí, or Fort Sumner, in southeastern New Mexico from 1864 to 1868. As we were separated from our beloved land, we were also removed from the foodways that had nourished us for generations. Fry bread became an emblem of this period—a provision created from necessity, for survival.

Today, fry bread is still a controversial topic in the movement for food sovereignty and decolonized diets. As Marcus Monenerkit, director of community engagement at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, sees it, “Fry bread has become the thread through which many non-Indigenous people have begun to appreciate actual Indigenous foods. . . . It’s a hook to get people to try other foods, sustainable foods that are Indigenous to the continent.” Monenerkit’s work at the museum has continuously involved building relationships in Native communities over a shared meal, and even Indian tacos.

No matter where on Turtle Island you live, there is likely a version of fry bread that exists. However, there are regional name differences—popovers in O’odham lands in so-called Arizona, fried bannock as far north as Saskatchewan, and so forth. There are also various garnishes that elevate the fry bread to taco. At the Indian Pueblo Kitchen in Albuquerque, Executive Chef Ray Naranjo, from Santa Clara Pueblo, created a menu “that mirrors the present-day food culture while being inclusive of Ancestral Puebloan ingredients.” His menu includes both the Navajo Taco, made with ground Navajo-Churro lamb—a nod to Navajos’ love of mutton—and the Tewa Taco, named for the language spoken by his own tribe and made with ground Native American beef.

Alana Yazzie, an Arizona-based Navajo food blogger originally from northwestern New Mexico, details the tenacity with which she worked on perfecting her dough recipe. It’s an effort that was fueled by watching her mother make meals for her growing up. In many families, making fry bread has become a litmus test for what it means to be an adult or caretaker. My aunties would say that’s how I knew I was ready to live on my own, once I could make a decent batch. While not an ancestral Indigenous food, it makes appearances in the work of many contemporary Indigenous artists.

Monenerkit says the best fry bread he’s had was made by a family friend’s grandmother back in his Comanche homelands years ago. “It was golden brown, so soft and fluffy,” he reminisces. “Almost like a Krispy Kreme donut in texture.” The joy of his memory is palpable as we connect on the phone. It takes me back to the best fry bread and Navajo taco I’ve ever had, my late grandma’s. There is no match to the golden, fluffy, slightly crispy texture of her fry bread. Unlike anyone else’s, you could eat her day-old bread and still be satisfied.

The power of food is not only that it fuels our bodies. Good food nourishes our hearts and souls. While the limited nutritional value and devastating origin of fry bread and the Indian taco can’t be refuted, what has made this dish hard to separate from our Indigenous communities is the care and love many put into the dough. The memories of birthdays and special occasions marked by my grandma’s fluffy golden bread are imprinted in my heart. While she’s been gone for a couple of years now, those memories of being cared for in her love language have to be enough to feed me when I miss her hugs, and her soft hands that shaped the soft dough. The truth is I will never taste another dish like hers. Maybe that’s the best dish, the kind that leaves you hungry, wanting more, long after the last bite and the last goodbye.

Jaclyn Roessel

Jaclyn Roessel is the president of Grownup Navajo, a company dedicated to sharing how Indigenous teachings and values can be a catalyst for change. She lives with her husband and their children in the Pueblo of Tamaya.