In late summer and early fall, green chile grabs all the headlines. But red, with its smokiness and subdued fire, is deserving of your attention year-round. The red chile pepper is a matured chile, and in every respect, from its dark red color to its tempered sugars, it wears that maturity like a tenured professor wears an old tweed jacket. The green is full of flame and impulsiveness, youthful energy to blaze out of the tumbling roaster and take on the world, but red has wisdom and sagacity, and when it burns, it’s a slow build to fire, like a loving grandfather pushed too far.

It’s hard to find a New Mexico resident who hasn’t at least considered hanging a chile ristra beside their door, but it’s somewhat more difficult to find one who uses the ristra for its intended purpose: drying out chile pods in New Mexico’s arid climate for use over the winter and spring. Many of us purchase powdered red, but once you’ve made the change to starting your sauce with whole pods, you’ll never look back. And it’s a simple-enough thing to do: hang your ristra and pluck the pods off as needed. But make sure you only purchase ristras that haven’t been treated with chemicals, and preferably find out what variety will be filling your stockpot in the months to come. Of course, you can also purchase whole pods in bags from the grocery store, but they aren’t nearly as pretty.

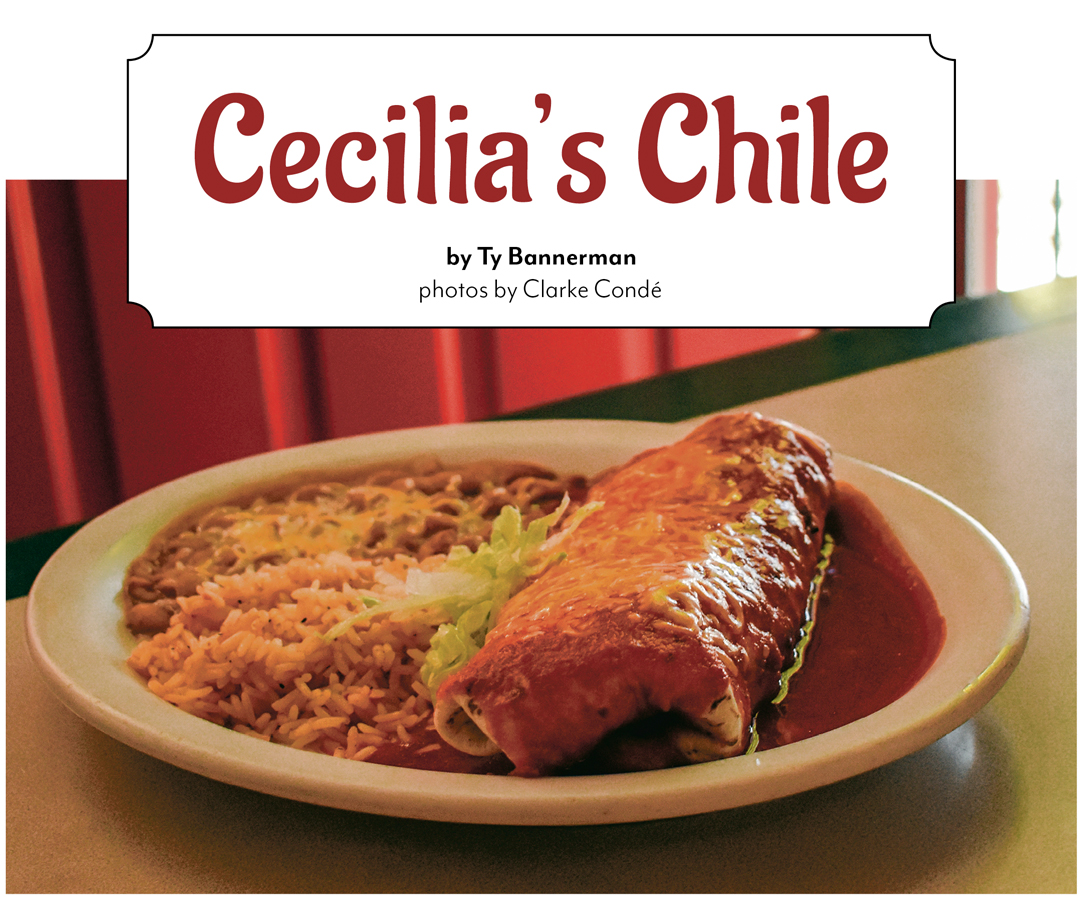

If you want to try red chile in its purest form, there’s no better venue than Cecilia’s Cafe, housed in a ramshackle turn-of-the-last-century building in downtown Albuquerque. It’s dark inside, and in the winter a pellet stove provides warmth to the handful of tables and assorted bric-a-brac festooning every surface; it feels like a throwback to an earlier age. Or at least it would if Guy Fieri wasn’t leering from a Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives poster on the back wall. He visited here in 2007 for season 5 of his show, the first of many national media outlets that have dropped by in the years since on their hunt for New Mexican authenticity.

I recently sat down with Cecilia herself to pry out her chile secrets.

She begins, she says, with a trip to New Mexico’s chile mecca, Hatch, some 180 miles from the restaurant. “It has to be triple X. I don’t get nothing but triple-extra hot,” she tells me, “and only this year’s crop.”

Heatwise, red runs more toward “warming” than “burning,” but that depends on the variety as well as the specific batch. If you dabble with triple X, like Cecilia, you may find your food tipping the scales toward full conflagration.

Once the pods are secured, they are stemmed and briefly toasted

in the oven. Then, the next day’s batch is soaked overnight until Cecila’s arrival the next day between 4 and 4:30 a.m.

Cecilia comes from a large family (she’s one of twelve siblings, where she learned to cook at her grandmother’s side). But she doesn’t use her familial recipe for the chile: her parents were very traditional in their approach to cooking, and she never cared for their red. “My mother always used manteca, or lard, and flour, but I never liked it that way. If I wanted gravy, I would make gravy. When you add all that stuff, it’s just gravy.” This is a matter of taste; many New Mexicans are happy to use flour and lard in order to make a red chile roux. But putting cumin in may well get you thrown out of the state.

Cecilia is a purist, and she only adds a few things to the chile: Mexican oregano, salt, and, most importantly, garlic. “You need the garlic to stop heartburn,” she says. “If you get heartburn from red chile, it’s because they didn’t use enough garlic.”

The pods and the water they soaked in now go into a blender, where they are chopped, skins and all. She blends all the ingredients until the paste reaches the right consistency, then she pours the mixture into a pot and cooks the chile a second time.

Once it’s cooked down, the red chile is ready to smother nearly any New Mexican dish.

If you visit Cecilia’s, you are of course welcome to try the red on huevos or enchiladas, but to truly highlight it, Cecilia recommends ordering the Fireman’s Burrito. The Fireman was named for the firefighters from station number 1 just around the corner from the restaurant—who, after having fasted to “make weight,” came in famished. It was their appetites that dictated the ingredients to Cecilia: chicharrones, eggs, potatoes, and beans in a homemade tortilla. This is her signature dish, and she recommends it for all comers. If you’re feeling brave and have something to prove, you can even order the large Fireman’s Burrito, which is ten pounds of food. “It takes two of us in the kitchen to handle it,” she says, “and I need twenty-four hours’ notice.” This is a novelty dish, made with two pounds of potatoes and ten eggs. Frankly, it’s only for the truly masochistic. If you manage to finish it within a half hour, it’s free and you get your picture on the wall, and, well, there aren’t very many pictures on the wall. “My first who successfully ate it took thirty-six minutes,” she says. “But we had one guy, Brandon Clark, do it in eight minutes and fifteen seconds. He’s on YouTube. He calls himself Da Garbage Disposal.”

To me, this sounds like a Cronenbergian nightmare. “But it’s not for people like you, mijo.” Cecila tells me. “It’s for firemen.”

Fortunately, the red chile also infuses the carne adovada beautifully, and I don’t have anything to prove.

Ty Bannerman

Ty Bannerman has been writing about New Mexico for over a decade. He is the author of the history book Forgotten Albuquerque and his work has appeared in New Mexico Magazine, Atlas Obscura, Eater, and the American Literary Review. He co-hosts the podcast City on the Edge, which tells stories from New Mexico’s past.