Four thousand years ago, the noodle was born. Quickly sweet-talking the planet, noodles forged their way through all corners of the globe, beguiling the Greeks, Persians, Asians, Europeans, and, eventually, the Americans. Slurp away, planet earth. With such a dizzying variety, where do we start?

Many of us are well versed in the diversity of the Mediterranean noodle. We plow hungrily through Italy’s vast cacophony of pastas, familiar or not: bucatini, fettuccine, pappardelle, tagliatelle, campanelle, fusilli, radiatore, farfalle, gemelli, orecchiette, conchiglie, ditalini, mezzelune, and everyone’s default, spaghetti. The consumption is often a habitual, timeless celebration of comfort and relish.

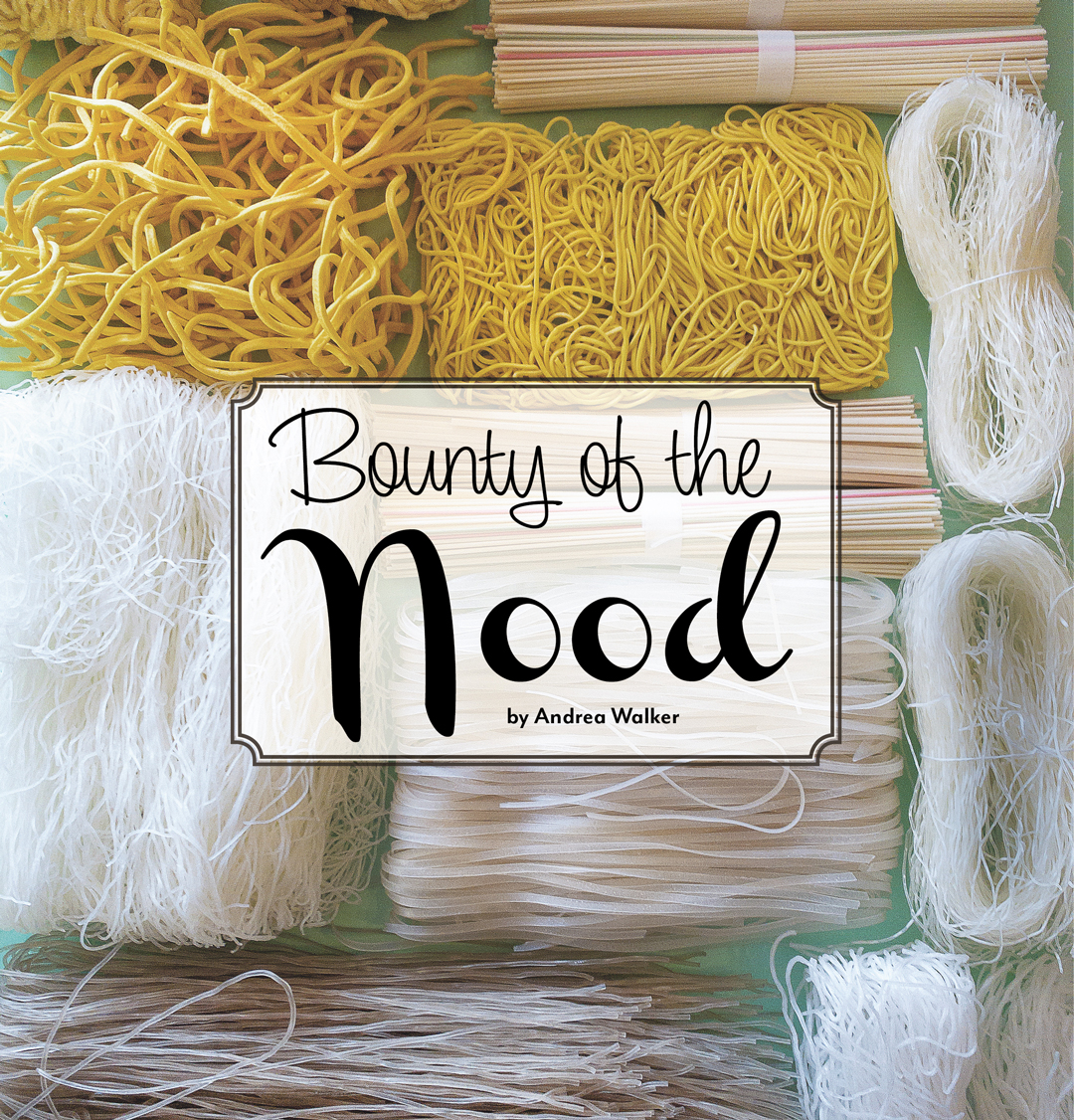

Pop into Vietnam, Korea, China, Thailand, Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Myanmar, Laos, or Japan, and you’ll find noodles created from rice, tapioca starch, wheat, buckwheat, egg, and mung bean starch—or a mash-up of several. Asian noodles are distinguished primarily by geography and noodle dough. In China, where noodles are thought to have originated, at least one variety—often wheat in the north and rice in the south—is a prominent staple on every table. Knead it, flick it, pull it, spindle it; fat or thin, stumpy or stretched, the Asian noodle is ever dynamic. You’re happy to fling dry Italian pasta in a pot of rumbling water to serve with a simple red sauce, but where do we go with the awesome array of noodles to be found at Albuquerque’s impressive number of Asian grocery spots?

Indonesia and Vietnam hosted my studies and work for years, but my most lucid and prized explorations were anchored in Southeast Asia’s cuisine. Seduced by the discovery of the unrevealed, the obscure, the offbeat, my search for noodles was tireless. Of all the Asian noodles I’ve tried, cellophane (or glass) noodles remain the most bewildering and quirky. Slightly elusive yet surprisingly versatile, glass noodles are fashioned from starch derivatives like sweet potato, tapioca, canna, or mung bean. Sold dry and reconstituted with water, they’re added to spring rolls, soups, or stir-fries. Glass noodles span much of Asia and are delightfully bouncy in dishes like Korea’s japchae, Vietnam’s miến gà, or served in a cold salad like Thailand’s yum woon sen.

You can tuck into Albuquerque’s 150 Asian restaurants and sample most of the aforementioned noodles, but if you didn’t grow up eating them, intimidation can linger when you step into the all-enveloping noodle aisle. You can always wander the often-overwhelming selection of Asian grocers like Talin or 999, but for an intimate glance at an equally varied display of glass noodles and all the rest, pop into the charming mom-and-pop A-1 Oriental Market located at 6207 Montgomery NE. Owner Ok Chu Shin has been operating A-1 for more than thirty years. Their repertoire leans mostly on Korean and Japanese products like homemade kimchi, fresh produce, savory sauces, dried mushrooms, and all the noods you could hope for. Their dry-noodle selection includes somen, Korean vermicelli, udon, wheat, egg, soba, rice, mung bean, chow mein, and more. For glass noodles, I haven’t found a more varied selection. Purchased dried, glass noodles are wiry and tend to be white or grey in color, and the prep isn’t as daunting as you might assume. For stir-fries or salads, soak the noodles in room-temperature water for twenty minutes, then strain. Or sling them dry into a soup and watch them plump with flavor. Their texture stands alone among noodles, and they have an appealing chewy bounce when consumed.

Chap chae at Ichiban. Photo by Stephanie Cameron.

Yukgaejang at Ichiban. Photo by Andrea Walker.

No need to pine over lost meals if becoming a savvy noodle cook is not your jam. Ok Chu Shin’s son, Josh Shin, runs their Korean and Japanese restaurant, Ichiban, which I’ve been smitten with for years. Their sushi, udon, teriyaki, kalbi, bibimbap, and red bean cheesecake all stand tall, but you’ll also find two memorable dishes that flaunt the flirtatious glass noodle. Chap chae (japchae) is a traditional spicy Korean dish with sautéed vegetables, protein, and sweet potato glass noodles. It is savory, sweet, salty, and delectable. Next, dive into the spicy broth of yook-gae jang (yukgaejang), a smoky brisket soup laden with glass noodles, egg, gosari (the young stem of fernbrake), and the gochugaru red chile flare that complements our own New Mexico red. Shiitake mushrooms and fernbrake bring a rowdy earthiness to the dish, and the broth mingles with sesame oil, fish sauce, soy, and scallions to make one fine hodgepodge of love.

With so many incredible recipes collected in the ether, glass noodles will likely become a staple in the pantry of anyone who gets to know them. Tucking into cooler weather and the fruits of a glorious New Mexico chile season, it’d be an injustice to not whip up a bit of yook-gae jang on your own. It’s as easy to make as our red chile posole, but with the provocative flare of Korean ingredients, all of which can be picked up at local Asian markets. The bounty of the nood awaits.

Yukgaejang (Spicy Beef Soup with Vegetables)

Adapted from Korean Bapsang: A Korean Mom’s Home Cooking

- 1 cup dried or fresh gosari (fernbrake)

- 1 pound beef brisket

- 1 onion, cut in half

- 8 ounces Korean radish, cut into big chunks

- 2 cups dried or fresh shiitake mushrooms

- 2 tablespoons sesame oil

- 3 tablespoons New Mexico red chile powder

- 7 garlic cloves, minced

- 5 tablespoons soy sauce

- 3 teaspoons soybean paste (optional)

- 1 tablespoon gochujang (fermented red chile paste), or to taste (optional)

- 10 scallions, cut into one-inch pieces

- 12 ounces bean sprouts

- 6 ounces glass noodles, soaked in warm water for about 20 minutes

- 2 eggs, lightly beaten

- Salt and pepper, to taste

- In a large pot, bring the meat, onion, radish, and whole mushrooms to a boil in 12 cups of water. Simmer, covered, until the meat is tender enough for shredding, about 1 hour. Remove mushrooms and set aside. Discard radish and onion, reserving the stock in the pot. Pull a string of meat off and check the tenderness. If still tough, cook for 10–20 minutes more. Remove meat from broth and shred into 3/4-inch strips. Spoon off visible fat. Reserve broth; there should be about 9–10 cups.

- If using dried gosari, boil in 4 cups water until tender (30–40 minutes). Let cool. Strain and cut strands into thirds. Cut the scallions into 1-inch pieces. Thinly slice the boiled mushrooms.

- In a large cast-iron or stainless steel pot, heat the sesame oil over low flame until hot, then stir in chile powder. Remove from heat when the oil turns red and the chile powder becomes a bit pasty. This only takes a few seconds, so be careful not to burn.

- Add the shredded meat, fernbrake, sliced mushrooms, soy sauce, and garlic. Sauté for 5 minutes over medium-low heat. Add the reserved broth. Stir in the optional gochujang and soybean paste, bring to a boil, and simmer over medium heat, covered, for 10 minutes.

- Toss in the bean sprouts and scallions and simmer, uncovered, for another 5 minutes. Lastly, add the noodles and simmer 2 minutes more, then slowly drizzle the eggs over the boiling soup for another minute until cooked. Salt and pepper, to taste. Serve with rice.

Andrea Walker

Andrea Walkeris an artist, cook, gardener, and explorer throughout New Mexico and beyond.