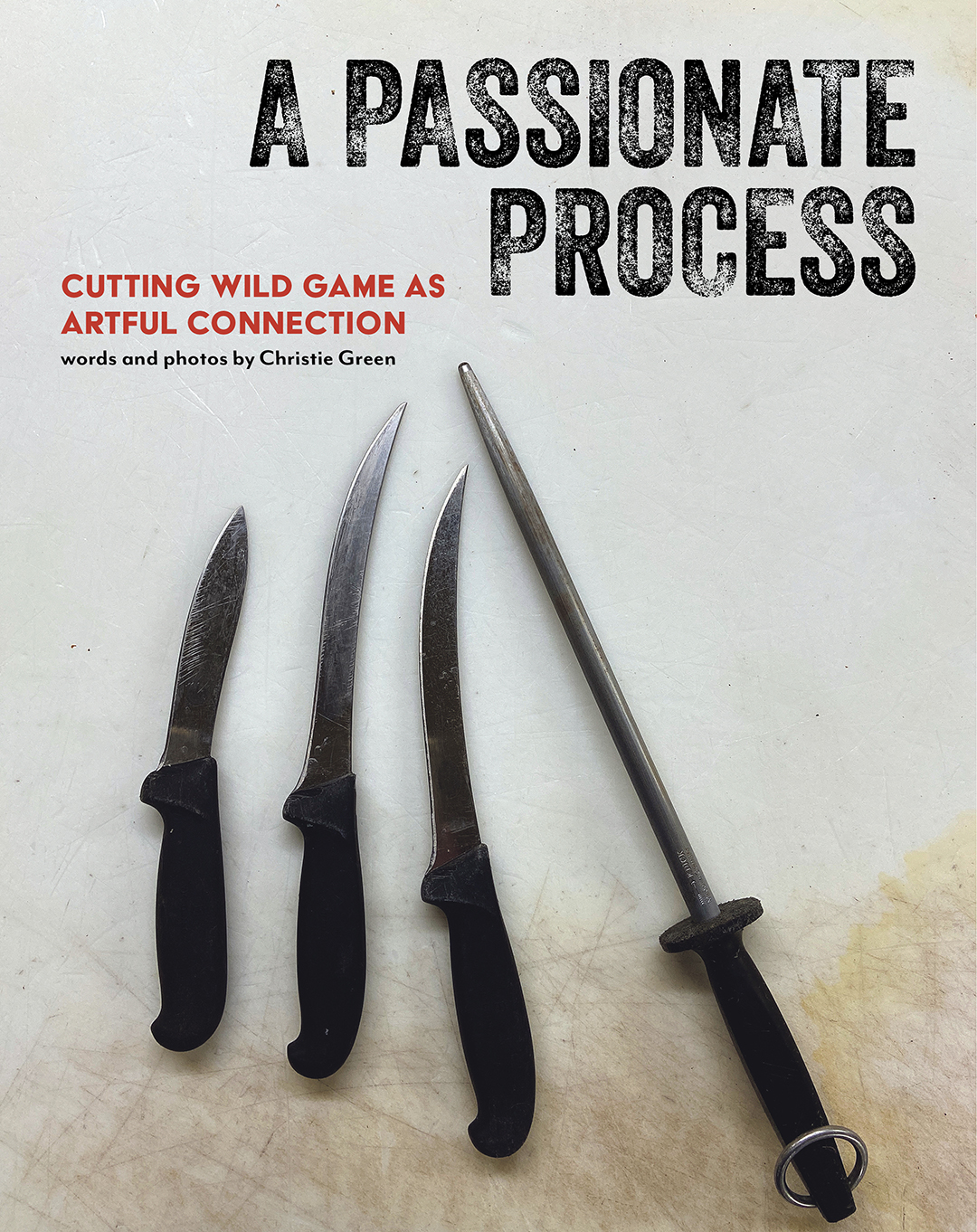

I pull butcher paper off the roll, tape it in sheets across the expansive counter, and sharpen two knives. We modified this kitchen space years ago to accommodate large-scale food processing, including cutting and packaging large animals like elk and deer. The counter has since become a place of utilitarian function—breaking down animals into packaged meat for the freezer, as well as cleaning, cutting, and canning bushels of fruits and vegetables from the garden—and communal gathering. Friends and family come to help with the labor, celebrate in the harvest, and share in the flavors of sustenance.

Exchanges across the countertop like “This elk comes from Tusas Creek near Tres Piedras” and “These white peaches made from the tree off the south portal” are typical banter that characterize harvest work parties and preface multicourse meals. Food connects us to place and to each other, and the cultivation, harvesting, hunting, and processing of food provides yet another opportunity for connection before sitting down to eat.

I first learned to butcher and process animals in my home state, Alaska, though I did not grow up hunting. Now, as a hunter in New Mexico, I choose to process the elk, deer, turkey, and other animals I bring home. I want to see the animal through, with my own hands, from “on the hoof” to “on the plate.” I believe that I owe this labor of love to the animal whose life I’ve taken, and I also am committed to clean, safe processing where I know exactly how the animal has been handled from start to finish.

Once the paper is in place, I hoist the elk hindquarter onto the slick, white surface, peel the gauzy game bag from her red-brown muscles, roll up my sleeves, and consider my first cut.

~

“I’ve been cutting meat since I was five years old,” says Albert Gomez of Wild Game Processing in Carlsbad. “It was our family business . . . they put us to work young!” I can practically see him beaming through the phone lines as he describes the standard package they offer, including steaks, backstrap cuts, stew meat, roasts, ground hamburger meat, fajita cutlets, and different types of sausages.

Gomez has owned and operated his processing company for about five years. Unlike some processors, he offers both wild and domestic meat processing. “We cut wild game during the hunting season and domestic [cattle, pigs, sheep, goats] during the off-season, so that way we’re busy year-round and can keep people employed.”

When I ask about the types of animals Gomez handles, I’m surprised by the diversity and volume. “We get a little bit of everything . . . elk, mule and whitetail deer, antelope, Barbary sheep, oryx, javelina, wild hog, bison—even wildebeest—from hunting ranches in Texas. We do just about everything and process an average of nine hundred animals a year. This year we’re going to offer fowl processing. I just bought an industrial plucker to meet the demand for butchering chickens.”

Gomez’s cheerful chatter draws me in. He feels like more than a butcher who handles meat safely and efficiently to get the job done. When he shares the types of sausages they custom craft, my mouth waters: Italian, bratwurst, four types of summer sausage, chorizo, and breakfast sausage. “There is the standard package we offer that includes some sausages. If folks want more types of sausage, there’s an upcharge for those,” he says.

“You know, part of the reason I haven’t brought the elk and deer I’ve hunted in for processing is that I’ve heard they get mixed in with other animals, that processors make more efficient work of the cutting by doing multiple animals at once. Is this what you do?” I ask Gomez.

“Oh no. No. That’s not at all what we do. That’s called batch processing. That’s for larger, more industrial operations. We handle each animal separately and individually. The animal you bring in is the animal you take home.”

One reason for that is to avoid cross-contamination with meat that hasn’t been handled properly in the field. “Bring a tarp!” he says when I ask about basic cleanliness and food safety practices. By having a designated clean space for the meat after field dressing the animal, hunters can avoid dirt and contamination. “If you take care of your meat,” Gomez asserts, “we’ll take care of your meat. Don’t bring us something dirty or mishandled.”

The by-products from Gomez’s business benefit a local dog breeder who comes to pick up the scrap meat and bones. “Nothing goes to waste. We make use of everything,” he adds.

~

Seven hours later, I’ve got one hindquarter, the backstraps, and tenderloins cut, wrapped, labeled, and stacked in the freezer. It’s late and time for bed, so I’ll save the other hindquarter and two front quarters for tomorrow.

I spend about an hour stripping the countertop of the blood-stained paper, peel the tape from the tile, and wad it all into the woodstove. I wipe down all surfaces with hot, soapy water, soak and scrub the knives, and spray everything down with diluted bleach.

The cutting board rests against the windowsill, ready for more cutting tomorrow.

~

When I dig deeper to get at what Gomez seems to love about his work, he pauses and says, “I just love these animals. I don’t want to see any animal get hurt. I wish them no harm. They died, you know. It’s the least I can do to treat them with respect and make the most, best use out of them.”

Alan Waggoner, proprietor of Springer Processing, echoes Gomez’s integrity and commitment. His sparkly blue eyes light up and he speaks gently, methodically, as he conveys his deep connection: “I love these animals. Hunters love these animals. We’re stewards and conservationists. We share a deep fondness for the hunt and the outdoors.”

Waggoner, too, has been processing meat his whole life and, inspired by his formative years in Future Farmers of America in rural Kansas, eventually earned a master’s degree in meat science. At Springer Processing, which he’s owned for two years now, he processes elk, deer, Barbary sheep, oryx, and antelope.

“I just always loved the wild meat best,” he says. “I like working with these animals. They’re the closest we get to the earth, our closest food source.” Springer Processing does not handle domestic meat, so business is slow when we meet during the off-season. Waggoner is able to operate with a city business license because there is no state regulation for wild game processing and federal regulation applies only to domestic meat processing.

Waggoner walks me through the processing plant and describes how the animal is hoisted from the truck, marked and weighed, moved to freezer storage, and then brought to the butchering table to be broken down. There are other stations for separating into steaks and roasts and for grinding and packaging. Finally, all packages are labeled and stored in a different freezer where trays are stacked, organized by customer name and animal number. Boxed, frozen meat is then picked up by the owner within two to ten days of drop-off, or shipped.

“We get the animal quartered or sometimes whole with hide. We don’t take anything that hasn’t been field dressed. We want hunters who have at least cared for their animals in that way. Either way, we’ll skin and quarter it. Then we weigh it and hang it in the cooler. This weight is how we calculate the processing price, which averages $1.35 per pound.”

The finished package reflects the customer’s specific request in terms of percentage of each type of cut. The average yield, Waggoner explains, is 45 to 55 percent of the gross weight of the meat. “So, say you bring in a two-hundred-pound cow elk, you’ll likely go home with about a hundred pounds of meat for your freezer.”

While still new to Springer, Waggoner has already recognized how the community comes together here. “We get hunters from all over telling us stories, asking questions. From newcomers and beginners to seasoned local hunters. And then there are folks who come in wanting scrap meat for their pets. One lady brings us cupcakes in exchange!”

Waggoner freely shares his recipes and methods, his suggestions for proportions of pig fat to mix in with elk for ground burger meat. “If someone is going to enjoy the product,” he says, “that’s what matters. I’m fine sharing . . . it doesn’t need to be my secret.”

~

By the evening of my second day cutting, I’ve put fifteen hours into processing this elk. The freezer is stocked. I lift the body cavity and stripped quarters onto the portal roof for scavenging birds and the succession of decomposers that will break the body down further. I set the skull to boil and begin fleshing the hide to send to the tannery.

Both Waggoner and Gomez gasp when I tell them how long it takes me to process an elk by myself. Waggoner exclaims, “What?! I can do that in about an hour or two!” He invites me in to come watch and learn. “You come on in anytime. I’d be happy to show you and share.”

I consider the offer while reflecting on my solo time, elbow deep with the elk. I know now that these folks who process meat aren’t just anonymous factory robots but real people invested in bringing the meat to its most impeccable finished state. Their hands touch, cut, handle, and wrap with personal care, lifelong knowledge, and artisanal wisdom.

I look forward to my next elk hunt this November. If I’m fortunate enough to harvest an animal, perhaps I’ll gather around the butcher blocks of these two processors to share in the labor of harvest and love.

Christie Green

Christie Green is a mother, hunter, and writer, and the principal landscape architect at radicle. Raised in Alaska and on her grandfather’s farm in West Texas, she now resides in Santa Fe. With food and water as catalysts, Ms. Green seeks to pique sensual connection and uncomfortable curiosity.